Invited and Implicated: Toward Critical Reflexivity in Non-fiction VR

By Aggie Ebrahimi Bazaz and Elizabeth (Liz) Miller, June 18, 2020

Introduction

As documentary filmmakers, the concept of power is essential to how we think about shaping and telling stories.

We consider ourselves digital radicals because we both proceed from a commitment to critical reflexivity as a means of leveraging documentary forms, techniques, and processes toward exposing and challenging power. We recently expanded our documentary practices to include 360-degree Virtual Reality (VR) documentary filmmaking.

In How to Tell a True Immigrant Story (2019), Aggie and her collaborators in the United States use experimental, aesthetic approaches to invoke self-reflective practices in members of dominant culture with regard to discourses of immigration and how those inscribe or reinforce power. In SwampScapes (2018), Liz and her collaborators in the United States and Canada are rethinking pedagogical uses of VR within an environmental justice framework and supporting a movement towards narrative sovereigntyi.

Our projects are quite different in form and theme but resonate with each other in their emphasis on collaboration and a desire to use the work for social change. We proceed from questions like: Who has access to 360 VR? What are the histories of VR and the values or aspirations that have accompanied each technological advance? What are the ethical frameworks in VR? How might immersive storytelling subvert rather than re-inscribe power inequities? What are the environmental considerations of the tools we are using, and how can we foster awareness about the infrastructures they come from and the waste they produce? What new forms and visual tropes might we discover through collaborative endeavors? What can VR do to liberate documented peoples (conventionally called “documentary subjects”) from the form’s “tradition of the victim” while addressing our most intractable social problems? Our process and our questions are ongoing.

Here in these reflections, we (Liz and Aggie) each describe our various production processes, collaborations, and theoretical foundations for documentary projects we produced in 360-degree VR. We describe our processes separately but within the shared space of this article. Separately, we demonstrate how techniques in documentary VR must be responsive to each project’s specific sociopolitical contexts and the nature of the social problems each project confronts (e.g. visibility and immersion mean different things in different contexts). And together, our overlapping approaches illustrate our conviction that, through community-informed projects that apply decolonizing models and critical scholarship to documentary work in 360 VR, we and our project partners might avoid a hyper-realized ethnographic gaze within documentary VR and instead optimize the radical potential of this immersive tool.

Critical Reflexivity in “How to Tell a True Immigrant Story”

View the Trailer

Aggie Ebrahimi Bazaz

“For the common soldier, at least, war has the feel—the spiritual texture—of a great ghostly fog, thick and permanent. There is no clarity. Everything swirls. The old rules are no longer binding, the old truths no longer true. Right spills over into wrong. Order blends into chaos, love into hate, ugliness into beauty, law into anarchy, civility into savagery. The vapors suck you in. You can’t tell where you are, or why you’re there, and the only certainty is absolute ambiguity.” (Tim O’Brien, “How To Tell a True War Story”)

Tim O’Brien’s “How to Tell a True War Story” is both an essay and a fiction contained in a collection, The Things They Carried (1990), which itself sits confidently between those two poles. Slippages in form are in fact one of the provocations of the piece and of the larger collection: how to tease out story from fact, the thing as it felt from the thing as it was, and whether those taxonomies matter in stories of war and all the categories and understandings it upends. “In war,” O’Brien writes, “you lose your sense of the definite, hence your sense of truth itself, and therefore it’s safe to say that in a true war story nothing much is ever very true.”

O’Brien’s act of writing asks us to think about the atrocities of war not by simply listing those atrocities, not simply in content, but in its form, by commanding the shape of the writing to be its own message, to be about us. We who experience war second-hand, the writing asks, what do our existing conceptual and story frameworks tell us is reasonable and, importantly, credible with regard to war? What truths do those ingrained frameworks exclude? How might our binaristic notions of morality, patriotism, and truth need to evolve to account for the “skewed angles” of war-time violence where “the only certainty is absolute ambiguity?”

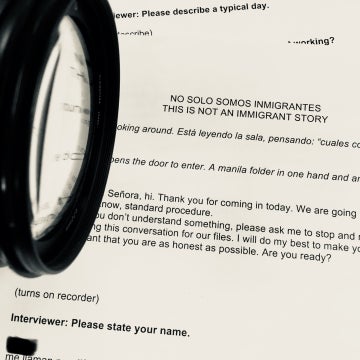

How to Tell A True Immigrant Story is a short, experimental act of critical reflexivity in 360 VR that applies strategies from O’Brien’s work and documentary scholarship to thinking through the limitations of our existing discursive frameworks pertaining to people and experiences categorized as “immigrant.” Who and which power structures are served by that term and how, the film wonders? What experiences, expanses, and creative expressions might the term preclude?

I began conceptualizing the film in the fall of 2017, when a group of collaborators and I were invited to participate in the Public VR Lab’s first-ever national cohort dedicated to using VR technologies to “gather and curate immigration/migration stories of Americans from pre-1620 through 2018,” with plans to incorporate those stories “into a visual XR timeline.” I am myself an immigrant to the United States: my single mother defiantly moved herself and her two children from Iran into dramatically reconfigured and isolated lives in the United States. As such, I’m personally invested in expanding public notions of citizenship and belonging.

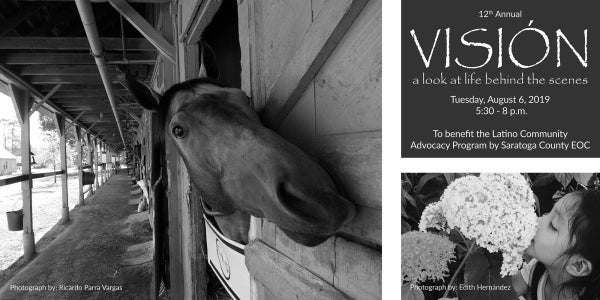

Since 2016, I’d been in fruitful creative collaboration with a group of artists and organizers in Saratoga Springs, New York, for whom the label of “immigrant” and its concomitant tensions of visibility were central to their lived experience. Our team was building on pedagogical models developed in the Estamos Aquí documentary photography workshop. Founded in 2007 by one of our collaborators, Krystle Nowhitney Hernandez, the workshop aims to “claim representational autonomy” in response to “stereotyped imagery of immigrants that […] pervade the attitudes and perceptions held within the local community” of Saratoga Springs. A networked storytelling project—Arrival VR—with a national cohort of support and distribution that could amplify Estamos Aquí’s commitments to creating new symbologies and ways of seeing, while using VR technology that is itself about the reaches and limits of seeing, seemed well-suited to our conditions. Such a project, however, also exposed the ways in which subscribing to the existence of “immigrant stories” might replicate the exact power relations-slash-imbalances that documentary purports to oppose.

Nestled in the foothills of the Adirondack mountains, Saratoga Springs and surrounding areas are predominantly white and affluent with charming main streets dotted with artisanal shops, bounded by pristine parks, and from which opulent residential arteries extend. The region is known as “a favored summer retreat for the nation and the world’s most privileged” for its many offerings, the most prominent of which is the Saratoga Race Course. Each summer, as Nowhitney Hernandez explains, the thoroughbred horseracing season brings in “nearly a million spectators” and “hundreds of millions of dollars in regional economic impact,” and as such, “is fundamental to the area’s economic vitality and cultural identity.”

The people whose labor upholds this foundational, vibrant economy are mostly folks of color from Mexico and Central and South America, many of whom migrate into the United States via guest worker visas for six months per year to “care for some of the world’s most elite race horses,” says Nowhitney Hernandez. Those who work with the horses live and work across the street from the public racing venue in an area called “the backstretch.” The backstretch houses not only the predominantly Latinx workforce—in barrack-style dormitories with communal bathrooms and no functional kitchens—but also houses the horses and their stables.

The backstretch is also a site for parking during the racing season, for morning exercises open to the public, and for a “behind-the-scenes” walking tour led by the National Museum of Racing, as well as several charitable organizations that offer various transportation, food, clothing, and faith-based and health care services.

Here we see a metaphor for ways that the community who live and work at the backstretch must navigate varying degrees of visibility. They may be invisible—in the shadow of the horses or passersby—or hypervisible, the source of some degree of ethnographic gaze, looked-in-upon during a behind-the-scenes tour for example. There is in either case little authentic encounter. As M., an Estamos Aquí photographer and member of the backstretch community explained in a conversation, when members of dominant culture look in on the community, they “see the horse and not the person carrying the horse.”

With the installation of the new presidential administration in 2017, this chasm of identities expanded. By the summer of 2017, the virulent anti-immigrant sentiment that began fomenting with the inauguration had materialized into an increase of ICE activity in Saratoga’s downtown and its surrounding parks and courthouse.

Our collaborators were hearing stories daily of devastating arrests downtown and subsequent deportation orders. Many were thus even more reticent to enter spaces generally coded by and for the white middle-class demographic and in which people of color might be hypervisible. Where once, even as late as 2016, visibility had been an important organizing strategy—undocumented and unafraid—visibility was now an open, urgent question—what will happen to our children?—or a silence entirely. Community members described feeling afraid to speak Spanish in taxi cabs and convenience stores for fear of being reported to ICE by inhospitable neighbors.

These are the two (at least) Saratogas in which we were working and which launch the film. To some, including the film’s first speaker, Saratoga is a “magical, mysterious, magnetic vortex,” full of inviting charms twirling about the beating heart of the city, the race course. And for those who work the race course or agriculture, those industries which support that beating heart, Saratoga is “good, but there are dangers here too.” This line is delivered by the film’s second speaker, a Latinx, Spanish-speaking woman, whose words act as careful rebuttal. I want to emphasize this word, danger. It’s not simply that Saratoga has its problems as would any small town. Rather, Saratoga is a site of lived danger that fosters a feeling of trespass for those who are labeled as “immigrant.”

To begin production for our 360 VR film, we began with a standard documentary approach: the interview. But in the political climate in which we were working, interview questions such as where are you from, how long have you been here, and what brought you here, exposed themselves as not only expository but ideological. As Trinh T. Minh-ha writes, the knowledge-making face of documentary works to “make accessible” those who are seen as alien. The interview in such a context is a space to position people within their proper roles, to “produce and represent social relations.” “Without their [documentary] benefactors,” Minh-ha writes, such communities are “bound to remain non-admitted, non-incorporated.” Here, the language of documentary is adjacent to customs control, both seeking admissions and incorporation, the positioning of people within their proper social roles. How then were our documentary interview questions offering something different from the immigration interview if central to both is, “Who are you and why are you here?”

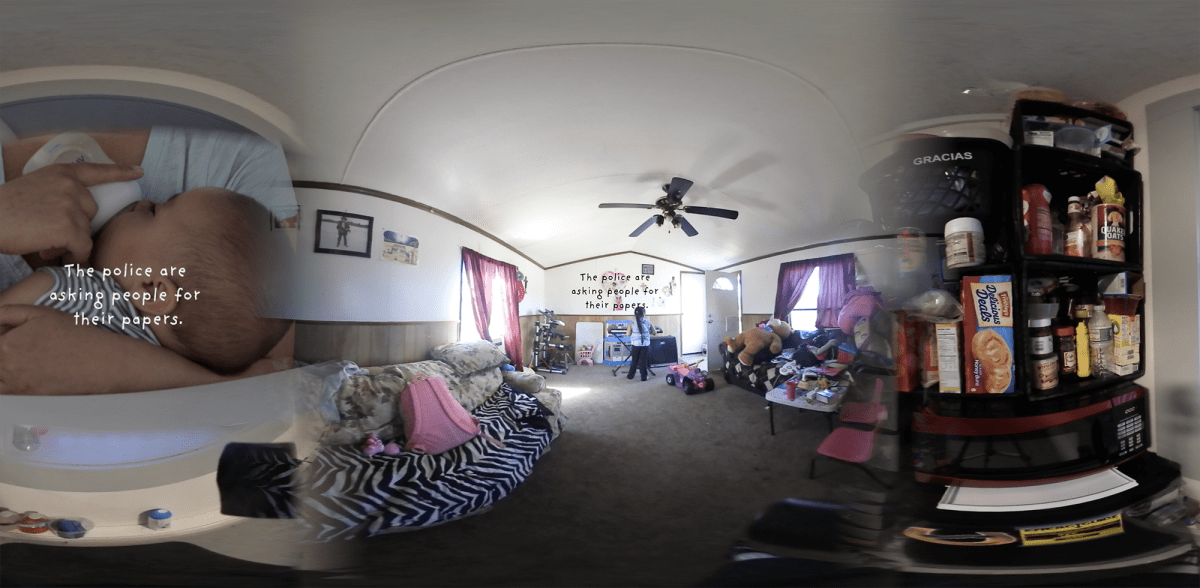

In direct dialogue with critical scholarship and borrowing from O’Brien’s techniques, one structuring device for our film became an interrogation room in which the focus is not only about interview content, but about interviews and their questions themselves as sites for the practice and replication of power. We aimed for ambiguity about the nature of the interrogation. It could be either a customs interview or a documentary interview, to draw parallels between these two practices of “incorporation,” a la Minh-ha.

In the interview, Karen Gomez, a non-actor, community organizer, photographer, and teacher in the Estamos Aquí workshop, performs the role of interviewee. She is met with scripted questions delivered by Matt Bagley who plays a well-meaning, white male interrogator. Our mise-en-scene included the recording technologies to highlight the space’s constructedness.

In the spherical space of 360 VR, the viewer can experience these two subjectivities and positions of power that not only represent aspects of social relations in Saratoga Springs, but also implicate documentary filmmaking and invoke the viewer’s own presence in this space: The viewer as (inter)viewer; the viewer as (inter)viewed.

While each interview question begins as something like information-gathering, the “interviewee” resists the data collection and launches into more meditative contemplation. When asked to speak her name for the record, Karen responds, “me llaman por diferentes nombres” (people call me by different names). This response refuses the (inter)viewer’s desire for the convenience of naming and asserts identities beyond the instrumentalized: “I am mother, I am son, I am river.” This is one way the film aims to support the transformative work of representational autonomy begun by Estamos Aquí over a decade ago.

Similarly, rather than celebrate the spherical frame’s promise of more to see, we disrupt acts of seeing entirely. The seamlessness of the 360 sphere is fragmented to prevent multisensorial immersion in an “unrestricted” field of view that supports feelings and fantasies of dominance and conquest while suppressing critical faculties.

All the lines in the film are taken from recorded or informal conversations with community participants and interwoven with verse written by community poet and collaborator Roga ‘74. The narration for the film, like the film and the process of its making, forms a chorus of voices and experiences that, through the use of poetry and lyricism, insist on community, on complexity, and on unpinning from under the categorizing documentary impulse. “And where are you from,” retorts that voice of resistance. “And to whom does this land belong anyway?”

In a recent screening of the film in Saratoga Springs organized by local entities and designed for white audiences, one audience member said, “I was an immigrant to that story.” The film confronted this viewer not with proximity but with disorientation, a feeling of foreignness, of being spoken to in a grammar not their own. Perhaps in this way we succeeded, if only momentarily, in disrupting that power relationship in which the experiences of people labeled “immigrant” are made accessible for white (inter)viewers.

Critical Reflexivity in SwampScapes and Circle Visions

Visit the SwampScapes Website

Elizabeth (Liz) Miller

Like Aggie, my own entry into VR 360 was an invitation to rethink traditional power dynamics and ways of representing social relations inflected by race, gender, and class. I specifically address these questions within an environmental justice framework.

My work as a VR practitioner interestingly began not through the act of making but through viewing. One of the first works I experienced was Nomads (2016), developed by the talented Montreal-based studio Felix & Paul. The stated objective of the project was to visit some of the “last remaining nomadic tribes” living in Mongolia, Kenya, and the Malay Archipelago. The directors had intentionally removed the presence of a narrating voice to offer users a new relational perspective. I put on the headset and found myself inside the wooden houseboat of a family from a Bajau tribe in the Malay archipelago.

I did experience a new sensation of closeness to this faraway place, but it was accompanied by an anxiety that I was simply implicated in a new form of voyeurism, harkening back to an uneasy ethnographic gaze of the past or a technologically facilitated “tourist gaze” of the present. I began to wonder about the social transactions and power dynamics that had shaped this encounter.

The experience raised questions for me about what critical reflexivity might look like within this immersive visual platform. If this medium could construct a sense of proximity, how might we as critical producers negotiate distances and account for the structural inequities in play around this immersive technology?

The opportunity to actually engage in a non-fiction 360 VR production and to grapple with these complexities came a few years later while in residence in one of the largest swamps in North America, the Everglades, as a visiting Knight Chair through the University of Miami. I wanted to use the affordances of new media to foster connection to a place that was threatened and largely misunderstood. Wetlands and swamps around the world have been sacrificed to pave the way for housing, agriculture and industry without much regard for what is lost. I was convinced that one of the biggest threats to wetlands was a lack of understanding of the role they play in capturing carbon, fostering life, and buffering us from uncertain futures. Before arriving in Miami, I had not anticipated that the SwampScapes project would involve spherical storytelling. My conception of 360 VR at the time was that it was a powerful medium for place-based storytelling but largely out of reach for both independent producers as well as most audiences.

My reluctance to engage in 360 VR was challenged by Kim Grinfeder, the director of the Interactive Media Program at the University of Miami. Kim is committed to environmental issues and had the technical know-how and equipment to make such a project. He won me over with his enthusiasm, and in collaboration with co-director Juan Carlos Zaldivar, we took on the challenge to integrate an environmental justice perspective into a non-fiction 360 VR as a pedagogical experience with our students and community partners. We wanted to know how we might connect place-based storytelling to a critical approach to 360 VR and, in doing so, cultivate connection to a place that is inaccessible to many but critical to us all. What kind of insights, complexities, and new ethical considerations might emerge by trying it out for ourselves?

To counter my anxieties about making a piece that would reach a very limited audience, we developed the project across several platforms, including a website that would be accessible to the general public. Over several months and in collaboration with university students, community organizations, and biologists, we developed multiple facets of our documentary project including a thirteen-minute 360 VR film, a VR companion piece, a website with 2D video profiles, an interactive sound piece called Swamp Symphony, a photo exhibit, and a study guide.

For the 360 VR component we conceived of the thirteen-minute film as an educational virtual field trip with an imagined target audience of urban youth with no means or interest in wading through a swamp. We emphasized the notion of a guided “field trip” rather than a tourist excursion to emphasize the critical and reflexive stance we wanted to assume both in the making and the sharing of the work.

Pedagogies of decolonization foreground the importance of learning the history of a place, the ongoing role of indigenous stewardship, and the importance of being invited to a place. We wanted to ensure that if we were hosting a virtual field trip or teleporting users to a fragile, sacred, or faraway place, we were careful about how a user entered the space.

For this project, we employed the device of “guides,” people with a deep relationship to the place, to situate the user in a respectful way. The guide would welcome the user and point out relevant details. For SwampScapes we wanted to move away from a solo guide or “character” and prioritized a polyphonic approach, emphasizing multiple voices and elements. Media scholar Patty Zimmerman (2018) suggests an advantage to a polyphonic documentary is the opportunity to gain new insights by what is side by side, juxtaposed, layered, or in relation.

We chose seven guides, each with a unique relationship to the Everglades, including Larry, an algae expert; Donna, a raptor biologist; or Betty, an indigenous educator and water activist. Each guide represented a different way of being and knowing in place, and each spoke to themes relevant to climate instability, including health, species extinction, and indigenous world views, respectively. We worked with each individual to develop scripts that helped contextualize the place but also demonstrated each individual’s unique modes of listening, being, and interacting with his or her surroundings. Our challenge was to find a meaningful balance between having the guides welcome and situate the user and letting users simply experience the presence of the place.

Indigenous scholar and pedagogue, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson suggests that for indigenous educators, meaning “is derived not through content or data, or even theory in a western context, which by nature is decontextualized knowledge, but through a compassionate web of interdependent relationships that are different and valuable because of that difference.” We hoped that, by integrating the perspectives of multiple guides in relation to these landscapes, we might invite and implicate each viewer as a witness to a place in time and a web of relations and shared responsibility towards an ecosystem.

Environmental justice speaks to the power imbalances inherent in environmental struggles and is a helpful framework to think through critical questions, such as, “Whose voices or perspectives are included?” Anishinaabe scholar Deborah McGregor suggests that in addition to considering how power imbalances between people take form in environmental injustices, we must also rethink our relationships to animals and plants and other beings. What additional perspectives might be incorporated into the project to re-center ways of relating to the animals and plants that live in the swamp? How might we use the 360 camera to challenge the logic of conquer, control, and fill the swamp? We positioned the camera underwater or high up in a tree to invite users to think like water or experience a scene from a tree’s point of view. We also staged scenes where the camera is set between an alligator and a guide to invite the viewer to inhabit the space between these two positionalities.

Throughout the process we practiced critical reflexivity by considering and trying to minimize the intended and unintended impacts that our project might have on the non-human and human protagonists that we were profiling. Part of our interest in a virtual field trip was to mitigate the potentially harmful impacts of human visitors on the ecosystems we were trying to draw attention to. But the notion of a virtual visit raised other questions. Might our simulated visit unintentionally “romanticize” an environment that is full of very real threats such as alligators, snakes, and mosquitoes? By developing a virtual field trip to promote a deeper connection to the swamp, might we inadvertently be promoting more screen time over an opportunity to explore a local landscape? And how might we communicate our concerns about the material waste of each headset?

Throughout the project we attempted to balance our curiosity for the medium’s potential with our conviction that our virtual field trip was not a replacement for outdoor education and that technology alone does not help to cultivate care. We began to explore ways to connect critical 360 VR practice, informed by environmental justice, decolonization, and participatory methodologies, with ongoing forms of critical media literacy and environmental education. We felt that our potential to build awareness would be realized through the curation of immersive media and the involvement of teachers invested in critical pedagogies.

Once back in Montreal, I was eager to discover how I might further explore my concerns about access. I wanted to transfer the skills I had learned in Miami with students at my home university, Concordia, and to share my 360 VR storytelling insights with the non-profit I have been collaborating with for the last four years, Wapikoni Mobile. Wapikoni is a Montreal-based Indigenous participatory filmmaking organization that offers training and equipment to Indigenous youth throughout Quebec. They have converted recreational vehicles into self-contained mobile audiovisual teaching studios, and they send urban filmmakers to rural Indigenous communities to engage in practices of co-creation. In collaboration with Kester Dyer and other students and faculty at my university, we have been offering summer media workshops for Wapikoni graduates that we call “Circle Vision.” Our approach is based on values of respect, reciprocity, and co-creation, and the project is part of ongoing efforts to decolonize academic institutions in Canada by engaging in mutually benefitting creative projects.

Kester and I worked with two students, Zaccary Dyck and Emily Trudeau, to develop a 360 VR workshop for Wapikoni participants. We spent five months exploring how we might make take advantage of the rapid technological advances that were making 360 VR technology more affordable. We explored open access 360 VR sound tools, wrote a how-to guide, developed a workshop, and read extensively about indigenous methods and land pedagogies. Jason Lewis, founder of Aboriginal Territories in Cyberspace (AbTec), reminds us that technologies shape the way we experience the world and are shaped by the identity and concerns of the people building them. Inspired by Lewis and the work of the AbTeC workshop series, we wanted to explore how we might structure our own workshop to invite experimentation and reflection about the intersections of 360 VR, circular frames, circular notions of time and space, and indigenous narratives and worldviews. Our challenge was to facilitate a space where the filmmakers and student mentors could learn from each other and foster new understandings and relationships. What new aesthetic forms or ethical considerations might arise from this pedagogical encounter?

We invited Daphne Boyer, an experienced Metis artist working in 360 VR for the first time to be our artist in residence for the workshop and offer mentorship. Daphne has been using new media animations to revisit traditional practices of women’s handwork to showcase Metis heritage and to bring analogue and digital methods into conversation. We invited four Wapikoni filmmakers who imaginatively used the circular frame as a space to reclaim language, to connect daily rituals with lost ceremonies, and to explore the use of poetry and land within 360 VR. Mikmaw filmmaker Naomi Condo, member of Gesgapegiag First Nation, and her collaborator Craig Commando, an Anishinaabe musician and filmmaker from Kitigan Zibi First Nation developed a script in anticipation of the workshop focusing on the circular frame as a device to connect the past and the present. In their finished film, a young woman begins her day with a smudging ceremony to honor her great grandparents and then asks a series of questions about how things might have been different if her ancestors had been allowed to perform these ceremonies rather than have them suppressed. Karen Pinette Fontaine used the circular frame as a poetic device to recover language, inviting viewers to share in her daily intimate rituals and an ongoing process of recovering her own native language. Mélina Quitich Niquay brought viewers to an urban wooded area and used a poetic narration to describe her feelings of dislocation, having moved from a more remote rural community to a larger nearby city to study.

One significant drawback of the experience was that the workshop took place in Montreal and not in the actual communities of the participants. We had to acknowledge the obvious limitation of being far from the sites where participants’ stories and experiences were rooted. Still it was an opportunity to begin to democratize a medium that has been largely out of reach for most of us and has the potential to become a tool for critical pedagogy and narrative sovereignty. Artist and scholar Courteney Morin points out the power of facilitating VR workshops for self-determined representation, suggesting that screen sovereignty is achieved when Indigenous people are representing their own stories and cultures and in doing so changing the potential and the trajectory of the medium.

Final Thoughts: Invited and Implicated

Because our theory of change suggests that mediation is as critical as any media object, we are also actively seeking out venues to continue the work of using our projects to educate, to foster deeper listening processes, and to engage in the grounded processes of social change and critical pedagogies. Aggie and co-producers Emily Rizzo and Krystle Nowhitney Hernandez have experimented with exhibiting How to Tell a True Immigrant Story within an intergroup dialogue model to foster critical self-awareness in white audiences around the ways that power and privilege show up in their thoughts about and relationships to those they consider “immigrant.” Liz and her co-directors are planning to share SwampScapes in classrooms and libraries to build awareness about climate change and are exploring how to expand a viewing experience from a singular headset to a collective experience.

In discussing our practices and processes, we hope to illustrate that critically-informed, relational praxis can be the site of transformative energy in any medium by creating a pathway for de-centering dominant (and domineering) worldviews (settler, white middle-class, Western, capitalist, human) and re-centering ways of relating and looking that aim to redistribute or at least to interrogate power and its machinations. In narrative forms, this might mean resisting the tropes of character identification, immersion, and empathy which “suppress” critical faculties in favor of experimental forms that can hold multiple perspectives, illuminate complexities, and expose “how audiences are implicated in the situations described.”

We believe that a collaborative framework can invite and implicate the viewer as part of a collective framework—not as part of the community, but as a witness to the potential of something larger than the self. In this way, non-fiction VR can prioritize relational approaches to time, places, sounds, and voices that resist capitalist world views and the neoliberal self. This approach is our radical intervention.

We have put these two pieces in conversation in this article, but we want to be in conversation with others who are also using VR in radical ways. Can we continue to develop models and practices that use VR to foster dialogue where it is not happening or shift behaviors and attitudes around places we may never visit? Can we use this medium to call forth other forms of listening? Knowing? Self-knowledge? Sensory knowledge? Emotional knowledge? Associative or ancestral knowledge? And in so doing, how might our understandings of issues, people, and ourselves and our responsibilities change? How might we, at the least, be asked to think anew about our acts of looking and listening?

Aggie Ebrahimi Bazaz | Assistant Professor, Film & Media Production | Georgia State University

Elizabeth (Liz) Miller | Professor, Communication Studies | Concordia University

We are grateful to Jean Burset for his invaluable support formatting citations and organizing endnotes for a previous version of this article.

Endnotes

i Indigenous screen creators in Canada define narrative sovereignty as a process of cultural expression and revitalization and as a means of contesting years of cultural repression, cultural appropriation, and misrepresentation. For more information see imagineNATIVE (2019) On Screen Protocols & Pathways: A Media Production Guide to Working With First Nations, Metis, and Inuit Communities, Cultures, Concepts & Stories