Video-Based Experiment Proves Successful at Brokering Peace Among Ex-FARC Combatants and Local Communities In Colombia

Five-minute videos showing ex-guerilla fighters co-existing with their new neighbors promoted peaceful reintegration.

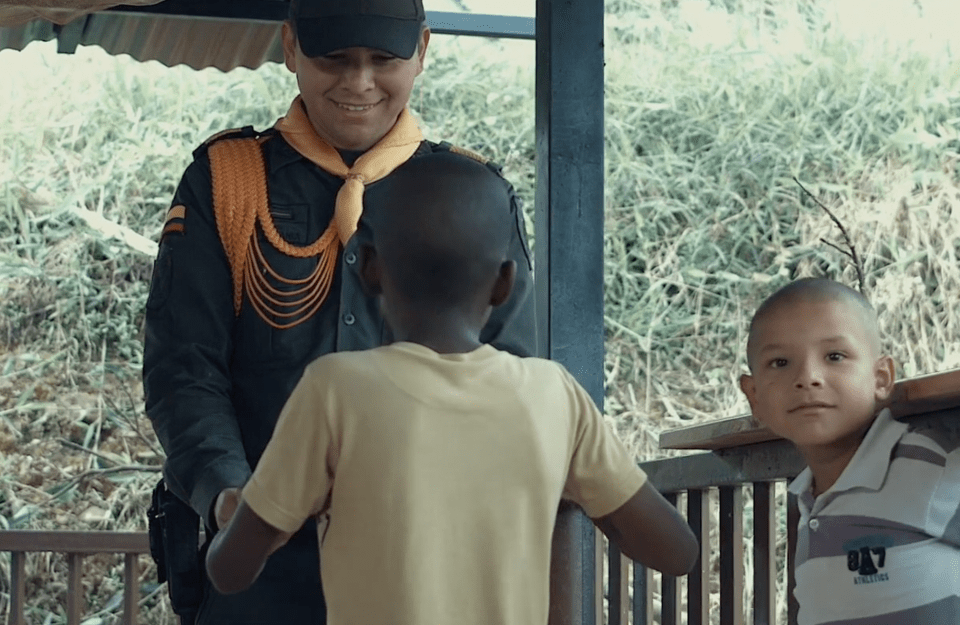

An image from the intervention video shown to promote peace between everyday Colombians and ex-FARC members (Credit: Pirata Films)

“Making peace” between groups in conflict is an appealing concept, but what does it take to actually do it?

A new study from the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab (PCNL) at the Annenberg School for Communication found that exposure to targeted media interventions – in this instance, a five-minute video – can bolster reintegration efforts between former enemies.

The newly published Nature Human Behaviour study, “Exposure to a media intervention helps promote support for peace in Colombia,” explores the impact of media interventions on brokering peace among former members of Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and non-FARC Colombians. It was the last major field research conducted by former Annenberg Research Associate Emile Bruneau before he passed away from brain cancer in 2020.

Bruneau observed many decades ago — not as a scholar but as a volunteer in Ireland during “The Troubles” and at the end of the apartheid in South Africa — that just because conflict resolution efforts should be helpful in particular contexts does not mean they will be in practice. As a neuroscientist deeply passionate about understanding the biological roots of conflict and applying research to promote peace, Bruneau was drawn to the internal multigenerational conflict between Colombians previously involved in the violence-ridden guerilla group and the rest of the population.

"We know that humans identify with characters through film and media, and we’re seeing that can be true of psychological interventions as well."

Bruneau worked with Colombian practitioner Andrés Casas, along with Boaz Hameiri (PCNL postdoctoral fellow) and Nour Kteily (Professor, Northwestern University), to test what impactful reconciliation initiatives look like.

After interviewing and surveying Colombians nationwide, Bruneau and Casas uncovered a widely-held negative belief that ex-FARC members didn’t want to reintegrate into society and were unwilling to give up violent tactics.

They then traveled to Antioquia, a region that had experienced some of the most intense fighting over the course of the conflict, and filmed interviews with ex-FARC members in a demobilization camp. These ex-FARC members were generally not only interested in peaceful reintegration, but were already finding ways to reintegrate by, for example, forming a soccer team, rebuilding local roads, and raising funds for poor villagers. The videos also showed their non-FARC neighbors who vouched for their successful co-existence.

With Colombian filmmakers, the research team created five-minute videos targeting different psychological mechanisms that served as barriers to successful reintegration. They held an intervention tournament with 10 different versions of the video shown to a large sample of non-FARC Colombians. (This experimental design is the subject of a new theoretical paper, "Intervention Tournaments: An Overview of Concept, Design, and Implementation," by Hameiri and PCNL postdoctoral fellow Samantha Moore-Berg.)

They tracked how Colombians’ sentiment toward the ex-FARC members changed after watching the videos. While all were effective, one in particular made Colombians more supportive of reintegration policies and less likely to dehumanize the ex-FARC. This made Colombians more willing to hire them, not discriminate against them in healthcare, and even donate money to charities supporting them. When the researchers spoke with the same participants 10-12 weeks later, the effects persisted.

The interventions increased empathy for the other side and combatted the misperception that people are unable or unwilling to change, says Kteily. All of this suggests that it is possible to meaningfully change how members of the public feel about reintegration in five minutes or less, with no actual person-to-person contact.

The findings underscored the potential to leverage the same ways of thinking that fuel people’s animosity to help de-escalate tensions and promote understanding. Kteily noted that even individuals’ engrossed facial expressions as they watched the videos spoke to the potential of targeted media to support peaceful reintegration efforts.

“It highlights the power of narrative through parasocial contact, which is to say that you're not necessarily having intergroup contact directly, but through a media intervention,” he says. “We know that humans identify with characters through film and media, and we’re seeing that can be true of psychological interventions as well.”

The magnitude and robustness of some of the effects supports the researchers’ argument that media interventions can be important tools used for helping everyday citizens embrace and sustain peace, according to Hameiri. “It really increased our confidence that these effects are not a mere statistical error, and that this approach has merits,” says Hameiri.

There is no one-size-fits-all intervention — a reality Bruneau continuously emphasized. Still, he saw the promise of testing scientific interventions within conflict zones across the globe and remained hopeful. He spoke of the subject on video at his home in 2019: “Maybe in fifty years we can have a menu of interventions, and we can place people into the intervention that might work best for them. And I think that’s an exciting possibility.”