Is Ethical Conduct Enough To Regain the Public’s Trust in Democratic Institutions?

By Alicia Fjällhed

In recent years, there has been a concerned discussion about actors who stray away from accepted moral conduct in their communication with the public. This was also a reoccurring topic of concern at this year’s Milton Wolf Seminar, accompanied by a parallel concern for the receding public trust towards democratic institutions. This text takes a closer look at the moral ideals for journalists and public diplomats often used as a stance to separate one’s own practices from the problematic conduct of others. From this point, the text moves towards a discussion whether such frameworks are enough to restore the public’s trust described as lost towards democratic institutions as trustworthy sources of information.

For the past 22 years, the Milton Wolf Seminar has engaged in discussions at the intersection between media, diplomacy, and journalism. This year was no different, starting from a common observation that “public trust in journalistic institutions has plummeted”. This was accompanied by another observed trend as “government actors across the political spectrum are reimagining their public diplomacy” in response to the increasingly hostile geopolitical landscape, politicised media landscape, and complex communication environments spanning from traditional to digital and social media. Journalists and public diplomats share the challenge of navigating an information milieu “characterized by dis/misinformation, fragmentation, decline and receding public trust in information sources” such as towards these actors’ own institutions.

Such concerned discussions include criticism towards actors found to be responsible for this development, often criticising actors not present in the same rooms such as opportunistic post-truth politicians, hostile foreign actors, or irresponsible social media platforms. Consequentially—as repeated in other forums—this year’s seminar discussion amounted to questions such as What sort of regulatory models for media platforms should be pursued? But, this text asks, what about us? Could the public’s distrust towards our institutions have something to do with not only other actors’ conduct but also our own? Considering our commonly agreed ethical frameworks which charts out the accepted leeway for one’s operations, would actions within such lines be enough to regain the trust lost from sceptical publics?

Same but different

To start these discussions, we first need to recognise the relationship between journalists and public diplomats. While representing different practices, the two share a communicative environment and intersect in part through their operations. From early forms of public diplomacy (see Cull’s text for a historic presentation), the rising influence of democracy led the public to hold a newfound power. This, in turn, led states to direct communicative efforts towards the public abroad—a bottom-up rather than top-down strategy for international influence. As Gilboa describes, this in parallel with the opportunities created through international broadcasting meant that diplomatic actors sought to use such mediums to convey their messages to the public abroad on a mass-scale.

At this point, some might want to emphasise that journalists operate in a national and international context, while public diplomats focus on foreign publics. While the latter is undoubtedly the emphasis in conceptualisations of public diplomacy, Stover shows how news media has also been used by diplomatic actors to influence a domestic agenda—taking the example of how the US state department when failing to convey their concerns to their administration for the bombing of North Vietnam “succeeded in stopping the bombing there after its warning was reported in the New York Times” (p. 115). As such, Stover argues that journalists in their capacity of telling a story about world events to the public “become active in the conduct of diplomacy”, operating “similar to the functions of a diplomat” by both gathering information as well as disseminating it in a way that influences public policy.

Beyond communicating through existing news media, public diplomacy has also found other mass mediums through which they can reach the public. Since the 90’s, social media has been the primary mass mediums discussed, as one could create an account to not only talk directly to but engage in conversations with the public. The latter is often described as an ideal opportunity but seldom an observed practice in empirical studies. Predating social media, public diplomacy actors have also created their own mass mediums as state-funded international news organizations—to different degrees holding journalistic independence from the state funding their operations.

Two ethical frameworks

Undoubtedly, journalists and diplomats share a practice in communicating their message to the public, and use media outlets to do so. However, as two different professions they are simultaneously bound to two different sets of aspired values in their respective codes of ethics.

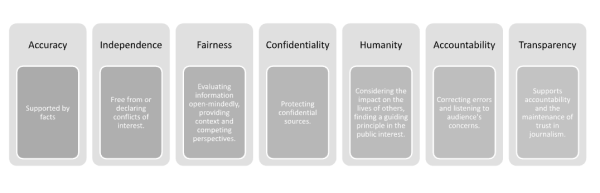

Patrick Wintour (political editor at the Guardian) described at the seminar how his profession’s ethical norms is broadly captured in the phrase ‘on the other hand’. By presenting several points of view, he argued that public journalism distinguishes itself from propaganda. Tying this to the ethical framework outlined in UNESCO’s handbook for journalism education, such principle would fit under the third value of fairness as one of seven points of departure for a code of ethics.

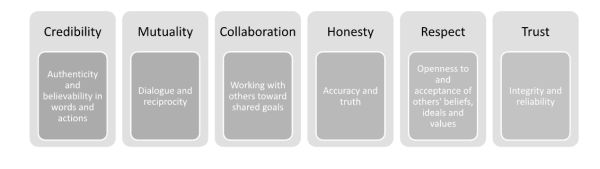

As for public diplomats, Gavin Sundwall (managing director for policy and planning at the US Department of State) emphasised that trustworthiness is tied to the concept of accountability. That is, as the US is promoting US values abroad, they themselves must walk their own talk. Fitzpatrick repeats this principle in her academic representation of credibility in combination with the value of trust as two of “six core relational values which might form the basis for a code of ethics for contemporary public diplomacy professionals” (pp. 39–40).

When comparing these two sets of professional codes of conduct, we see how they not only differ from one another, but also share similarities. Both emphasise the importance of speaking the truth (in values of accuracy and honesty), in different ways seeking to be a trustworthy voice (in values of independence and trust or credibility), and both emphasise the importance of taking multiple perspectives into account (in values of fairness or accountability in the first set and mutuality or respect in the second).

The ethics of each profession is also found in the one’s relation to the other. Sundwall, for example, emphasise how diplomats ought to make themselves available to journalists, not only to provide information but also to listen. For journalists, the above presented code of ethics emphasises the importance that one remains independent in one’s reporting, which too includes influences from state actors. This independence was also a subject for critical discussion at this year’s seminar—centred around debates about a type of state-funded news outlets perhaps better described as mediums for state propaganda. But as Dr Wright emphasised during the seminar, this represents merely one of several types of state-funded international broadcasters. While there is indeed always a link between the medium and the state, there is a difference in how independent these journalists are in their reporting.

In a recent publication from 2020, Dr Wright and colleagues showed through 52 interviews how journalists from state-funded international news organizations legitimize their relationship with the democratic or authoritarian government funding them, finding three reoccurring narratives. Either they differentiated their own practices from that of a common Other—repeatedly returning to Russian RT as a case of the unethical—alternatively they “deployed the ambiguous notion of ‘soft power’ as an ambivalent ‘boundary concept’, to defuse conflicts between journalistic and diplomatic agendas” or argued paradoxically that their funding from states actually provided them with greater “operational autonomy” (Wright, Scott, & Bunce, 2020, p. 607) Moving from a simple distinction between propaganda and soft power, the authors, however, emphasise that there is a grey spectrum of practices in-between. From such acknowledgment, the paper found that “by deploying deliberately narrow definitions of ‘propaganda’ as well as the conceptually ambiguous notion of ‘soft power,’ journalists were able to sidestep more complex and troubling questions about the relationship of their work to the operation of state security and intelligence” (pp. 623–624).

Are these ethical guidelines enough?

As initially emphasised, the construction of an ethical ‘we’ or ‘us’ tied to practices reflected in above presented codes of conduct is continuously contrasted against an unethical ‘they’ or ‘them’ who deviate from such norms. I would argue that these ethical frameworks have been constructed with the aim to build trust among the public—towards journalists and public diplomats respectively. This trust constitutes the foundation for one’s operations as without trust, people would not have a reason for bothering to listen in the first place, nor by extension will believe what these actors say to be true. Why, then, is it not working? Or, in light of the introductory descriptions of a rising distrust against the same institutions, a perhaps better point of departure would be to ask—why was the trust lost in the first place?

One repeated explanation is that the development is due to external factors and actors. As emphasised at this year’s seminar and numerous other forums in the past few years—a common explanation is that we have entered a post-truth environment where facts do not convince people as they act based on emotional instinct. We have found many examples of actors actively taking advantage of such environment, seeking a strategy intended to mislead the public. Such actors are continuously the subject of criticism at seminars such as this, criticising both such actors’ actions as well as the social media platforms’ inability to keep these actors away from influencing the digital public debate.

However, adding to these external explanations, is it possible that there are also internal factors influencing the receding trust towards democratic institutions? Returning to the ethical codes of conduct as frameworks intended to build trust—could the deteriorated trust be the result of cases where we have deviated from our own ethical codes? Or, perhaps, could it be that the critical public disagrees that this ought to be the moral standard in the first place?

Perhaps the external and internal factors should not be considered alternative explanations, but rather together paints a more complete picture of the situation. Indeed, some actors engage in campaigns to undermine the public’s trust towards democratic institutions—for example by pointing to real, honest mistakes made by such institutions, or alternatively inventing events which never happened where one deviated from one’s moral values. Similarly, we see how actors actively seeks to undermine the public’s beliefs in the validity of the same values. How do we deal with that problem? Is it enough to hunt down those seeking to do us harm while simultaneously repeating our own truths in campaigns where we strive to educate the public in media literacy programs by presenting rational arguments for our own framework’s validity—or do we have to seek another strategy to regain the public’s trust in our institutions?

My own suggestion would emphasise the pre-existing value embedded in these ethical frameworks of seeking understanding of this Other’s perspective. This does not mean that we need to agree with the one we are engaging in conversations with. But if we stop engaging with some voices, stop listening to what they have to say and stop recognising their existence in our communities, they will not see a reason for building the relations with us upon which trust is built. This is, however, not a painless process as it means that we need to engage in conversations with people who are convinced that the earth is flat and that women should not have the same rights as men. Of course, we cannot abandon our sense of truth and ethics—but to rebuild the trust with the publics described in concerned discussions at this year’s seminar to be declining, we need to recognise that there are publics whose opinions we do not share but we nonetheless must find a way to have a conversation with.

References

Cull, N. (2006, April 18). ”Public Diplomacy” Before Gullion: The Evolution of a Phrase.

Fitzpatrick, K. R. (2013). Public Diplomacy and Ethics: From Soft Power to Social Conscience. In R. S. Zaharna, A. Arsenault, & A. Fisher (Eds.), Relational, Networked and Collaborative Approaches to Public Diplomacy (pp. 29–43). New York: Routledge.

Gilboa, E. (2008). Searching for a theory of public diplomacy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political Social Science, 616(1), 55-77.

Stover, W. J. (1981). Journalistic Diplomacy: Mass Media's New Role in the Conduct of International Relations. Peace Research, 13(2), 113–118.

UNESCO. (2018). Journalism, ‘Fake News’, and Disinformation: Handbook for Journalism Education and Training.

Wright, K., Scott, M., & Bunce, M. (2020). Soft Power, Hard News: How Journalists at State-Funded Transnational Media Legitimize Their Work. International Journal of Press-Politics, 25(4), 607-631.