Doctoral Candidate Eleanor Marchant Pursues Dissertation Fieldwork in Kenya

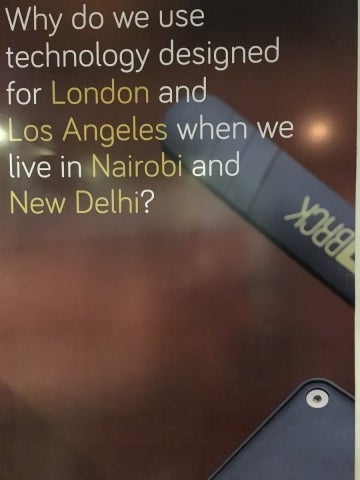

Marchant's research focuses on narratives around technology and innovation in Kenya, and who controls and shapes them.

Eleanor Marchant makes a good point: six weeks into a year-long ethnographic field project may not be the best time to talk about it.

After all, the aim of ethnographic research is not as much to test a hypothesis, as to immerse yourself in a community and let your findings emerge over the course of the experience. And Marchant, a fourth year doctoral student at the Annenberg School for Communication, has chosen to study for her dissertation a subculture far from the ivory tower of University City: the technology sector in Nairobi, Kenya.

Marchant’s bracelets clink over the Skype connection as she speaks about her dissertation research from her apartment balcony overlooking a small river valley. Her research may be far from its conclusion, but Marchant’s journey is already a fascinating one.

Of particular interest for her are the narratives around technology and innovation in Kenya, and who controls them and shapes them. For example, how does the media, both foreign and domestic, portray the world of tech startups in Kenya? How do the tech incubators and organizations there talk about their work? What about the Kenyan tech elite, many of whom are heavy Twitter users and actively engage online?

To begin her exploration, Marchant is based at iHub, which was created in 2010 as the first tech hub/pre-incubator on the African continent and describes itself as a “community hub for techies.” (Today Marchant estimates there are nearly 200 organizations in Africa identifying as tech hubs and incubators, many of them modeling themselves on iHub.) As part of her immersive experience, Marchant is contributing to some research projects within iHub, helps out with events held in the space, and participates in meetings to shape the organization’s PR strategy. All of these areas shape how iHub is seen by the outside community and thus are of interest to Marchant’s research.

“I’m interested in iHub in particular because it plays a really important part in the discourse about technology made in Africa,” says Marchant. “If you Google ‘innovation in Africa,’ iHub is one of the big examples cited by international media — and iHub has been very good about positioning itself that way. As I look at the ethnography of this broader tech community, it’s the perfect place to be situated.”

For example, Marchant recently attended a startup competition held in part in the iHub space and run by the American incubator 1776. It was an interesting mix, she recalls, of high-energy American VCs, World Bank employees, African entrepreneurs from across the region, and iHub staff who manage the space. Similar events are held at iHub all the time, and its space because a nexus of interaction between the many different people who make up the Kenyan tech community.

The American narrative of Silicon Valley-style startups and entrepreneurs focused on profits seems to be a dominant one in Kenya right now, she says, as competitions like the one run by 1776 demonstrate.

But alternately, Marchant sees large corporations like IBM, and donor organizations and NGOs like UNICEF, USAID, and the World Bank also opening their own “innovation labs” In Nairobi.

Companies like IBM are clearly interested in profits, Marchant explains, but they often use the language of the development sector to describe their higher aims of helping Africans and solving African problems. NGOs, meanwhile, are seeking to support new technology that will further their own development goals, using many practices of the for-profit sector, like the innovation lab model itself.

“Calling them ‘labs’ and specifically using terms like ‘innovation,’ shows this mixing of discourses from for-profit and non-profit communities that have often been quite antagonistic to one another – and still are in many ways,” says Marchant.

She is also interested in what she’s calling “micronarratives,” stories of individual people and companies.

One of the most glittering success stories for Kenyans is the mobile network provider Safaricom and its mobile payment application M-Pesa, which is one of the leading ways to transfer money by mobile phone not only in the developing world, but also globally.

“M-Pesa figures heavily as one of the first pieces of technology that made people think there’s cool stuff coming out of Africa,” says Marchant. “It is often seen as having put Kenya on the map, in a way.”

Marchant is also looking at companies like Ma3Route — pronounced “ma-THREE-route” — that are focused on very local problems, like tracking Nairobi’s horrendous traffic. While Google Maps or Israeli-owned Waze may seem similar, Ma3Root argues that it is rooted in a Kenyan understanding of the problem and knows its consumers and its city better. For example, Kenyans often use different names for places than what appears on Google Maps — crucial if you’re looking to get from Kibera Town to the Central Business District, or to avoid roads that are poorly paved or falling apart, something that the Google Maps model is unable to keep track of.

Small breaks in communication can have large effects on tech companies. Uber, Marchant notes, has struggled in Nairobi, in part because Kenyans tend to have longstanding relationships with their taxi drivers, trusting them with their safety, but also to run small errands like independently retrieving items left at home.

Gaining people’s trust and access in ethnographic field work — not to mention one’s own bearings in a new culture — can be a challenge, but it helps that Marchant has experience both living in and studying Africa.

After getting her Master’s Degree in Political Science at NYU, where her thesis focused on the role of information in political change in Benin and Togo, Marchant worked for the press freedom organization, The Media Institute, in Nairobi from 2007 until 2008.

After returning to New York, she worked for Media Development Investment Fund, a socially-responsible investment fund that focused on media outlets in developing countries. She quickly found that researching the impact of their investments was her favorite part of the job, and so she applied to Ph.D. programs.

She didn’t get accepted.

“It was an eye-opening moment,” she admits. “I had been out of academia for a long time and I didn’t have academic references. My writing style was more corporate or programmatic than academic.”

Then she met Annenberg Professor Monroe Price, who advised her to try a different kind of work experience before applying again. For a year and a half, Marchant worked for Oxford University’s Programme in Comparative Media Law & Policy. There her main research project was to study the role of Somali expatriates living in London and how the satellite programming they produce there for a Somali audience affects domestic politics.

The next time she applied to grad school, Marchant had several options. She chose Annenberg.

While Ph.D. programs in the U.K. dive right into dissertation work, skipping the lengthy coursework phase, Marchant knew she needed that methodological and theoretical groundwork that Annenberg could provide.

Now in Nairobi, she particularly finds herself thinking back to Internet Policy with Price (“He brings in real world problems that are happening right now”); Media Ethnography with Professor John Jackson, who became her advisor; and Traditions of Ethnographic Research with Laura Grindstaff, a Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Davis, who was a visiting scholar in Fall 2014 with Annenberg’s Scholars Program in Culture and Communication.

Fieldwork, however, was often in the back of her mind. Marchant went back to Nairobi again in the summers of 2013 and 2014 to conduct preliminary research for her dissertation giving her a stronger foundation and better networks with which to begin the year-long core fieldwork she is doing now.

“For as long as I can remember, I’ve been interested in how people from different backgrounds communicate with one another,” says Marchant. “I grew up as a dual American/British citizen and have lived in both countries, and there's something about the tension between two nationalities that I find really compelling and interesting. It made me want to go to places that were as different from where I had grown up as possible.”

Marchant plans to spend the next year conducting interviews, attending events, participating at iHub, collecting a wide variety of textual material, and sifting through all of it - basically the meat that makes up an ethnographic project.

“I want to try and let the field speak to me,” she says. “Over time, I’ll reconnect with the theory and see patterns, pull it together bit by bit, and go back to the field. It’s all very iterative.”