When Young People Seem to Make Threats on Social Media, Do They Mean It?

A new app from SAFELab helps teachers, police, and journalists interpret social media posts by BIPOC youth and understand which threats may be real.

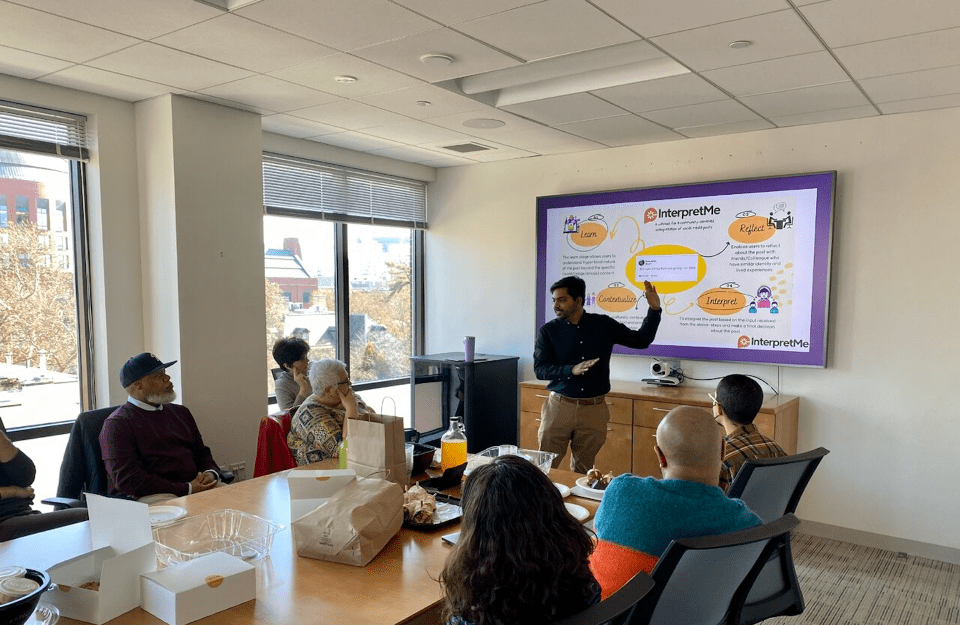

Professor Siva Mathiyazhagan presents SAFELab's new app: InterpretMe. (Photo Credit: Carson Easterly, School of Social Practice and Policy)

In New York City, law enforcement regularly monitors the social media use of young people who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), compiling binders of Twitter and Facebook posts to link them to crimes or gangs.

Something as benign as liking a photo on Facebook can be used as evidence of wrongdoing in a trial, so when police officers misinterpret social media posts — which often include slang, inside jokes, song lyrics, and references to pop culture — it can lead to serious consequences.

To prevent these kinds of misinterpretations, SAFELab, a transdisciplinary research initiative at the Annenberg School for Communication and the School of Social Practice and Policy at the University of Pennsylvania, has launched a new web-based app that teaches adults to look closer at social media posts: InterpretMe.

The tool is currently open to members of three groups — educators, law enforcement, and the press.

“These are the people who come into contact with young people regularly and have influence over their lives,” says Siva Mathiyazhagan, research assistant professor and associate director of strategies and impact at SAFELab. “Yet many of them don’t have the cultural context to understand how young people talk to one another online.”

A Closer Look at Social Media

Development of the app began when SAFELab Director Desmond Upton Patton, the Brian and Randi Schwartz University Professor at Penn, was an associate professor at the Columbia University School of Social Work in New York.

Students from the School of Social Work met weekly with youth at the Brownsville Community Justice Center, a community center designed to reduce crime and incarceration in central Brooklyn, asking them for help in interpreting and annotating social media posts made by people their age.

“The young people at the Brownsville Community Justice Center understood how emojis, slang, and hyper-local words are used online,” Mathiyazhagan says. “Their insights were key to building the platform.”

The SAFELab team used this pseudo-dictionary created by the students to create online social media training for teachers, police, and journalists.

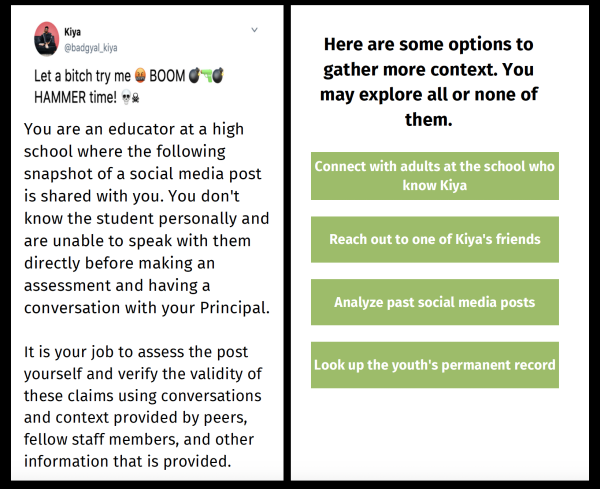

During this training, users are placed in a fictional scenario in which they encounter a potentially harmful social media post, such as a student seeming to be depressed or potentially violent, and must decide how to react.

While walking through the scenario, users gather context about the post, by doing things like looking at the young person’s previous posts or asking friends about their social life. At the end of a module, a user must decide how they will proceed — what they’ll say to their editor or principal about the student — and are invited to reflect on the reasoning behind it.

SAFELab tested the training with 60 teachers, 50 journalists, and 30 law enforcement officials in phase one.

Before and after the training, they all took surveys to judge how bias might affect their social media interpretation skills. Across all groups, bias scores decreased after using the training, Mathiyazhagan says.

A Web App is Created

InterpretMe is built on the insights the SAFELab team gained after creating and testing their training modules. Instead of walking users through a carefully crafted scenario, InterpretMe allows users to upload real life social media posts and then takes them through a set of exercises built on the SAFELab training.

After uploading a post, educators, police officers, and members of the press are walked through five steps:

- Learn: Users are prompted to learn more about the author of the post by looking at their social media engagement, interests, and other activities.

- Reflection: Users are asked to reflect on the post as if they were an immediate family member of the poster. They are then asked to reflect with a friend or a colleague who has a similar identity and lived experiences of the poster.

- Contextualize: Users are asked to consider the “social circumstance, cultural background, and linguistic expressions” behind the post and then whether the post was made under circumstances of mental health challenges and whether the post was influenced by mass media content like song lyrics or movie lines.

- Interpret to Act: Users are prompted to share their final interpretation of the post.

- Act: Users choose whether the post may cause no harm, possible harm, or probable harm.

After completing the exercise, users are sent a report of their interpretation.

InterpretMe 2.0

SAFELab plans to incorporate machine learning into the next version of InterpretMe, Mathiyazhagan says.

The SAFELab team has long been experimenting with AI. With the help of both computer scientists and formerly gang-involved youth in Chicago, they created a machine-learning model trained to detect gang signs, slang, local references, and emotion in the hopes to prevent violence.

While the model is based on data from Chicago, it could be expanded to include context for any area, the team says.

“Through artificial intelligence, we might be able to not only speed up the interpretation process, but also fill in cultural gaps,” says Mathiyazhagan.

A single person might miss song lyrics in a Facebook post, but a machine trained on community insights could flag them and stop a misunderstanding from happening.