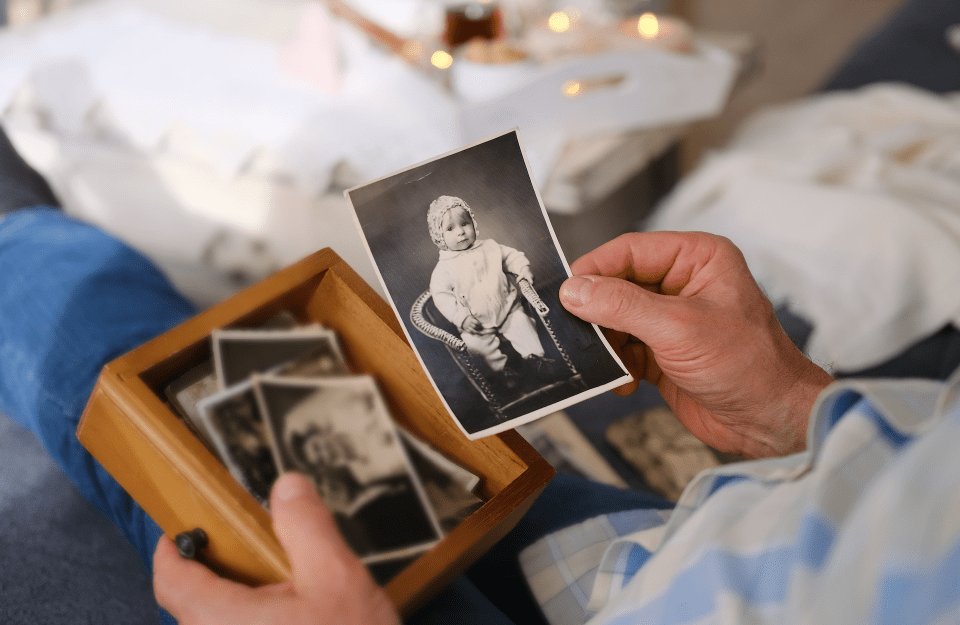

What Do Our Ancestral Family Ties Say About Our Political Beliefs?

A new study finds that the stronger your ancestral family ties, the more likely you are to hold right-wing cultural policy preferences.

The first institution we experience in life is family. As long as humans have existed, they have gathered in groups in order to survive — to pass down knowledge, lend protection, and form bonds. Not only does the institution of family help us survive, it has a strong hold on our political beliefs and attitudes.

A recent study from Neil Fasching and Yphtach Lelkes of the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, finds that the family structure of one’s ancestors — sometimes dating back thousands of years— reliably predicts their political beliefs today. If you come from a family line with strong kinship ties (who typically live with extended family and marry within their community), you’re likely to hold right-wing cultural values, and among some, left-wing economic attitudes.

“Interestingly, we find evidence that the association isn’t just with the individual beliefs,” says Fasching, a doctoral student studying political communication. “It plays out even at the country and legislative level. If a country’s population is rooted in close, tight-knit families, that country is less likely to pass LGBTQ-friendly laws, for example.”

Food, Disease, and Stranger Danger

Modern family kinship structure is determined by many factors, the researchers say, but most commonly, it is based on who family members are allowed to marry, geographic distance to extended family, and trust of outsiders.

These structures can date back to early civilization, when hunter-gatherers searched for game and Neolithic humans farmed crops and bred animals. Hunter-gatherers tended to have relatively weak family ties due to their need to travel to find food. It was easiest for these societies to revolve around the nuclear family, rather than establish permanent settlements with extended families and strong kinship ties.

Further, hunter-gatherers had to call on others for help when disasters struck or their hunters were unsuccessful. Because of this, they had to cultivate outgroup trust, and learn to accept strangers, which led to the evolution of universal values such as impartiality, fairness, and individual rights.

Farming societies, on the other hand, lived on permanent settlements, housing extended families together due to the cooperation needed to harvest crops, raise animals, defend their land, and build irrigation systems. These groups developed values that favored in-group members, such as respect for elders, obedience, and loyalty, to encourage cooperation and prevent shirking from duties.

From Paleolithic to Present

In order to trace the effects of ancestral kinship strength on contemporary political attitudes, Fasching and Lelkes assigned “kinship tightness scores” to over 20,000 second-generation immigrants living in 32 European countries. They chose second-generation immigrants in order to disentangle the respondents’ current location from their ancestors’ location.

The researchers crunched the numbers, using data on individuals’ beliefs, values, ethnic groups, and the degree to which a person’s ethnic group has historically depended on hunter-gathering versus agriculture, to determine the association between right-wing beliefs and family structure. Fasching and Lelkes also measured individuals’ political engagement.

The researchers found that stronger kinship tightness is linked to a preference for right-wing positions on cultural attitudes, but the links between economic attitudes were a bit more complicated — it depended on one’s political engagement. Among those who are less engaged in politics, tighter ancestral kinship structure is associated with left-wing economic attitudes.

“The link between kinship tightness and right-wing cultural attitudes and left-wing economic attitudes makes sense. Research has shown that those with a closed value system consistently espouse left-wing economic attitudes, even though right-wing economic attitudes tend to go with right-wing cultural attitudes in Western democracies,” Fasching noted.

Kinship and Policy

The researchers also examined the connection between kinship strength and national-level policy decisions. They chose two issues — legal protections for LGBTQ communities and social safety net policies.

Their findings? Kinship strength is strongly associated with more anti-LGBT laws. Countries low on kinship tightness, such as Norway, Finland, Germany, and the United States, were much less likely to have implemented anti-LGBT laws, while countries high on kinship tightness, such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Grenada, and Liberia, were much more likely to have anti-LGBT laws.

“While policy decisions may seem like they're driven by current or transient factors, our research shows that public policy is also deeply rooted in the cultural fabric of a society,” says Lelkes, Associate Professor of Communication at Annenberg and Co-Director of the Polarization Research Lab and the Center for Information Networks and Democracy. “Ancestral family kinship structures are a part of that cultural fabric and can shape the fundamental values and social norms that underpin our societies. These structures were formed based on the environment in which our ancestors lived, and can have a significant influence on the policies that are ultimately adopted.”

The relationship between national-level kinship strength and safety net policies was also significant. The researchers used on data the amount countries spends, as a percentage of GDP, on social assistance. Moving from weakest to strongest kinship ties increases the amount of social expenditures as a percent of GDP by 1.06 percent.

The researchers aren’t yet sure how kinship strength affects political beliefs.

One possibility is that kinship ties shape a person’s basic values system and that these values are what drives the relationship between kinship strength and specific political attitudes, the researchers say.

“It must be said, though, that culture is not destiny,” Fasching says. “That is, even within ethnic groups there is significant variation in policy attitudes and the effect sizes are smaller than other typical predictors of policy attitudes, such as education and age.”