Ten years later, examining the Occupy movement’s legacy

For Jessa Lingel, a decade after Occupy Wall Street’s beginnings presented an opportunity for reflection, which she led this fall semester in a new course.

Photo by Eric Sucar / University of Pennsylvania

On Sept. 17, 2011, a group of young activists descended on Wall Street to protest the gaping economic inequality in America. With the rallying cry “We are the 99%!,”—meant to highlight how the richest 1% of the population dominated the U.S. economy— the Occupy Wall Street movement grew not only within New York’s Zuccotti Park, but also in protests throughout hundreds of towns and cities in the U.S. and across the globe.

It was a watershed year for social movements, from the pro-democracy uprisings of the Arab Spring to Spain’s anti-austerity movement Los Indignados, both of which served as inspiration for Occupy Wall Street.

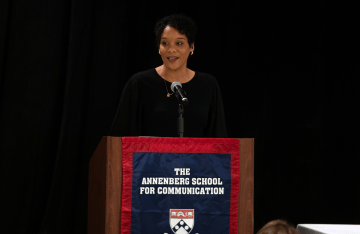

For Jessa Lingel, an associate professor at the Annenberg School for Communication and in the Gender, Sexuality and Women's Studies Program who participated in the Occupy movement in New York City, the 10-year anniversary presented an opportunity to reflect on its legacy, which she did this fall semester in her new course, We Are the 99%: Media and Memory of Occupy. The seminar looked at everything from the legacies of Occupy and other movements around today’s activist efforts, to how Occupy reshaped digital activist practices, to where the movement failed and where it succeeded.

“Occupy was an important movement for me as a young person and really helped me find my path with different kinds of activist work,” she says. “I wanted to bring awareness of that movement to a new generation of students, and connect Occupy to a larger activist history that they are much more familiar with.”

The enduring lessons of a movement

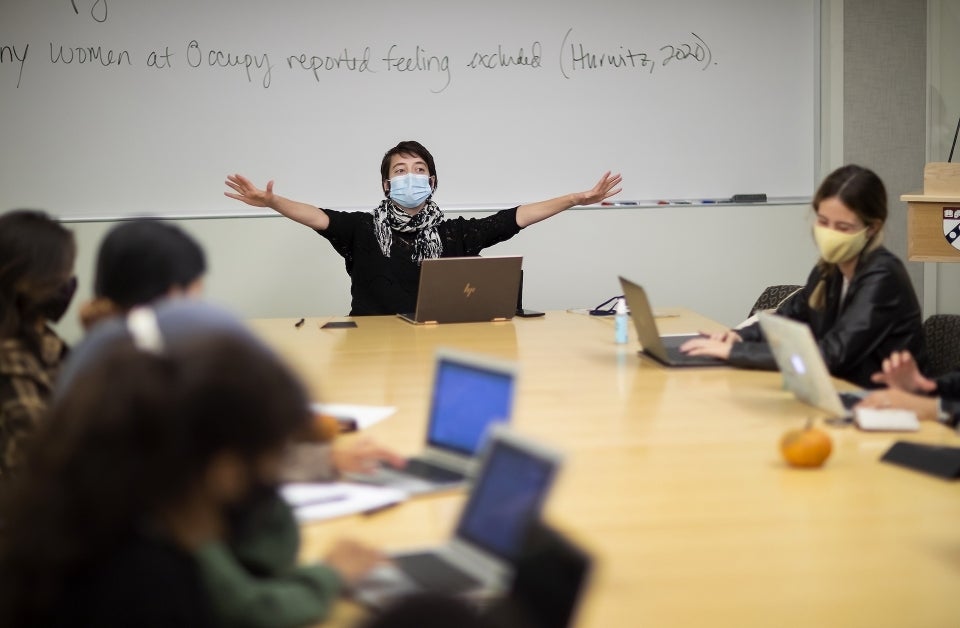

In the midst of an activist movement, it’s impossible to know what practices, technologies, and ideas will have staying power, and which ones will fade away, Lingel says, and the discussion-based seminar is a chance to take stock. The class focused on Occupy’s use of media and technology, and students learned fundamentals of social movements theory, analyzed the particular efforts and ideas of the Occupy movement, and developed a richer understanding of activist media.

“I wanted to bring awareness of that movement to a new generation of students, and connect Occupy to a larger activist history that they are much more familiar with.”

Coming on the heels of the racial justice protests of 2020 after the killing of George Floyd, the class was particularly relevant to students, most of whom participated in marches that summer.

“For students who are interested in continuing the work of the 2020 social movements, learning about Occupy is important for their own academic understanding of social movements and also for their own lives as activists,” Lingel says. “Any protest will be more successful if they learn lessons from previous uprisings that had some shared goals.”

They also discussed how police manage different types of protests depending on the makeup of the crowd (Lingel points to the Jan. 6 rioters’ treatment by police compared with that of nonviolent Black Lives Matters protesters), the role of social media in protest history, and how activism can build community.

Occupy wasn’t the first movement that was digitally documented—there was the 1999 World Trade Organization protest called the Battle of Seattle, and the Republican National Convention protests in New York in 2004, she notes—but with the rise of smartphones in the United States, Occupy was one of the first movements that was so widely captured on social media.

Lingel ran the class as an activist space and molded some of the classroom rules and policies around the norms of the Occupy movement: Students decided as a class what the due dates would be for their assignments and they suggested readings to add to the syllabus or topics they wanted to delve into more deeply.

“It was a bit more work for me because I had to respond on the fly, but on the other hand I was trying to signal to them that the classroom can also be a form of community,” she says. “One week we collectively decided to go to a protest on campus, rather than talk about the readings. It’s important for them to get that experience of building consensus together.”

The student experience

Logan Shalit, a senior in the College of Arts and Sciences from Los Angeles studying Philosophy, Politics and Economics, says he stumbled upon the class while scrolling through communications courses.

“Most of my classes up until now have been very scientific-based, but it’s my senior year and I wanted to take a communications class. I was intrigued by how this course studied social movements,” he says. “Especially in light of the Black Lives Matter protests after George Floyd and all the events that happened last year, I felt like it was my duty to take a class that would educate me about protest.”

He says he really didn’t know much about Occupy before the course, since he was only 11 years old when it was happening, and also never learned about the Arab Spring until this course.

“I’m honestly quite shocked that I was never educated on what either of those movements were about, especially considering how important the Arab Spring was in the development of some of those countries’ democracies,” he says.

He’s also been fascinated to learn about how social media platforms were used as tools and had pivotal roles in both movements.

“My generation is very focused on ourselves when it comes to social media, like how many ‘likes’ we get on Instagram, but in movements like Occupy or the Arab Spring, people used Facebook and other social media as a tool and they were able to gather tens of thousands of people to their protests,” he says. “I’ve just never viewed social media through a communications lens like that, and it’s been really eye-opening to see how much power it can hold.”

The fact that Lingel herself was at the Occupy protests in New York has been impactful, he says.

“It’s really cool that our professor was at the protests and can share her firsthand experiences and emotions, and helped me understand it more deeply,” he says.

Nathalie Marquez, a junior from Katy, Texas, majoring in communications, says she took the class because it seemed like a good opportunity to learn about the movement from a professor who she really enjoys and respects.

She says she was surprised by how the conversations the class had about Occupy can apply to other social movements and how they put into new perspective what those movements accomplished and what they failed to do.

Back in 2011, critics of Occupy pointed to the movement’s lack of specific demands or plans for next steps as problematic. Ten years later, some credit the movement with inspiring the “Fight for $15” push to raise the minimum wage and creating a political climate that helped the rise of presidential candidate Bernie Sanders.

“The largest takeaway I have from this course is that I used to think of movements as succeeding or failing in reaching certain goals or quotas. This class has led me to understand that there’s nuance in what we consider a win for a movement and there’s nuance in progress,” says Marquez. “Sometimes it’s worth doing something, even if you don’t get exactly what you want at the end of it. There’s still progress.”