Penn Students Research Which Americans Are Most Isolationist — and It May Not Be Who You Think

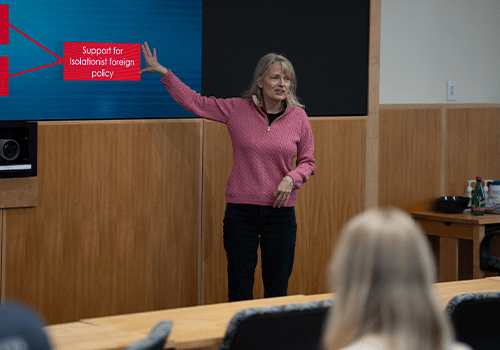

Prof. Diana Mutz’s course, designed to teach and implement research methodology, discovered a major shift in young Americans’ isolationist views on foreign aid.

Photo Credit: Chuttersnap / Unsplash

There are plenty of commonly-held stereotypes in American politics. For example, conventional wisdom dictates that Republicans are more “America first” than Democrats, and older generations are more isolationist than open-minded younger generations. After all, younger people have grown up in a smaller world, where global communications and transportation make knowing about and caring about international affairs far easier.

Professor Diana Mutz, who has been studying American political attitudes for decades, thought young people would be especially internationalist and concerned about global problems as a result. But research she conducted last semester with her undergraduate students turned that idea on its head.

Mutz’s course, “Media, Public Opinion, and Globalization,” asked students to design studies that investigated Americans’ opinions on globalization – examining attitudes toward issues like immigration, international trade, and foreign aid. Their initial data, collected by students conducting individual interviews, surprised Mutz: It found that American adults ages 18-30 tend to favor isolationist foreign policy, regardless of where they fall on the political spectrum, when compared with Baby Boomers, aged 60+.

“At least for the last half of the 20th century, Americans 60 and older were more isolationist than younger adults,” says Mutz, the Samuel Stouffer Professor of Communication and Political Science and director of the Institute for the Study of Citizens and Politics at Penn. “But now things have reversed. So what happened and why?”

The students noted that the version of isolationism for Americans 18-30 is not the typical “America First” worldview of the past, although they are more likely to think the US should generally stay out of world affairs. Instead, their isolationism based on the idea that imposing American-style democratic values abroad is racist and arrogant. But it also stems from their seriously low levels of trust in the US government, far lower than for older Americans. For example, younger people felt that America’s efforts to “help” other countries through foreign aid were more about its own self-interest than the well-being of foreigners.

“It's the paternalistic, condescending sense that the U.S. knows what other countries need more than the countries themselves do – that the U.S. is arrogant in their assumptions about what it means to help,” says Mutz, who recently published the book Winners and Losers: The Psychology of Foreign Trade.

Although younger Americans have a lot of characteristics that traditionally predict high levels of internationalism – such as racial tolerance, international trust, and more liberal political views – among adults under 30, these characteristics point toward wanting to avoid being involved in international affairs. “The more racially egalitarian you are in younger generations, the more isolationist you are,” Mutz says, “and the more racially egalitarian you are in older generations, the more pro-internationalism you are.”

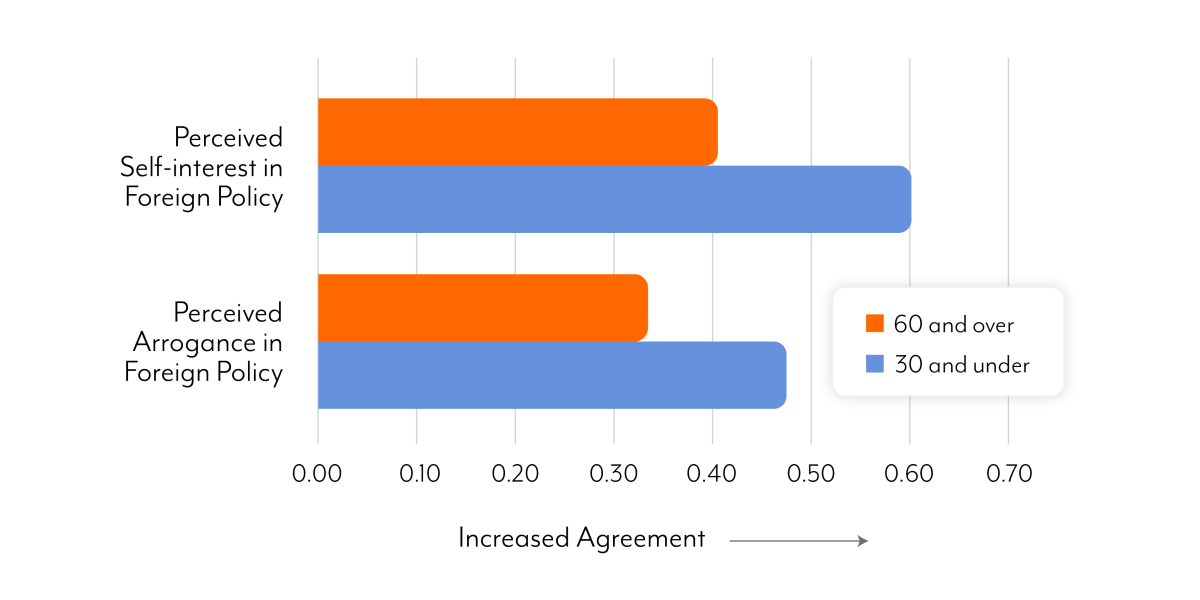

After their initial findings, the students contacted a survey research firm and designed questions asking about traditional measures of isolationism as well as their new theories about young people’s perceptions of arrogance in U.S. foreign policy as well as perceptions of how much self-interest enters into U.S. foreign policy.

The survey research firm recruited 1,000 participants, and returned data to the students for analysis.

The findings confirmed the students’ initial observations: Those 30 and under saw U.S. foreign policy as much more self-interested and arrogant than Americans over 60. (See chart.)

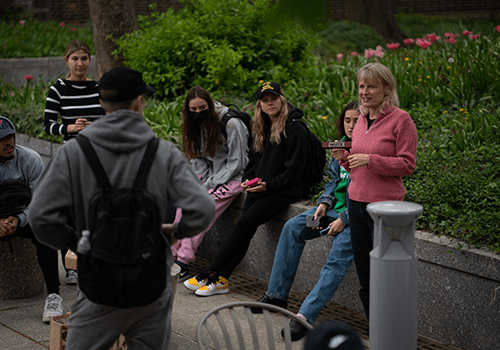

Students have a theory on why their generation is so different from those of the past: social media commentary. Their initial findings have shown this to be true, Mutz says. “The heavier social media user you are, the more isolationist you are in your foreign policy attitudes.”

Valerie Hanna (C’23), a Communication and Psychology double major in the class, didn’t expect her peers to embrace isolationism. “This finding surprised me,” she says, “given the importance my generation gives to issues such as climate change, immigration, and human rights, which will require global communication and collaboration in the years to come.”

But Samantha Delman (C’22), a Political Science major in the class, says the finding makes sense. “My group has hypothesized that young people may be more isolationist because we don't want the US to be seen as an exploitative ‘world policeman,’” she says.

The war in Ukraine, however, posed an interesting twist, and showed that opinion can shift on specific issues.

“One of the things I didn't anticipate that happened last semester was the Ukrainian conflict,” Mutz says. “And so a group of students designed an experiment embedded in this study that involved attitudes toward whether or not the U.S. should be doing more or less to help Ukraine.”

The students created an emotional two-minute video promoting U.S. aid to Ukraine, and it did indeed prove effective in encouraging people, regardless of age, to be more supportive of U.S. involvement in Ukraine. It was particularly influential for those who reported low levels of interest in politics, says Mutz, probably because they had not been tuned into the latest news.

“The students were very excited to see the findings, and so was I,” Mutz says. “The most fun part about research is not the hard work up front, but getting to see how it turns out.”