Penn in Latin America and the Caribbean

The sixth annual conference centered on the theme of ‘Shared Narratives: Arts, Culture, and Conflict.’

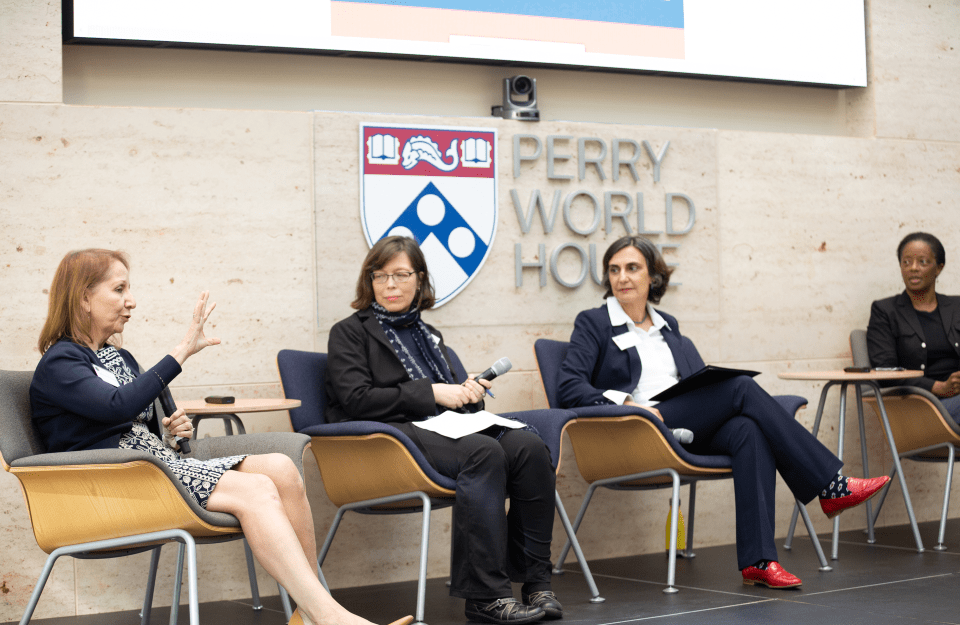

From left to right: Antonia M. Villarruel, Margaret Bond Simon Dean of Nursing at Penn Nursing, Emily Hannum, Professor of Sociology and Education and Associate Dean, School of Arts & Sciences, Tulia Falleti, director of the Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies, Class of 1965 Endowed Term Professor of Political Science, and Senior Fellow Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, and LaShawn Jefferson, executive director of Perry World House, at the conference opening plenary. (Photo Credit: Scott Spitzer)

From rapper Bad Bunny’s protest songs in Puerto Rico to food as resistance in the Dominican Republic, the arts are dynamically linked to cultural commentary in Latin America. Penn in Latin America and the Caribbean (PLAC) centered on this theme of “Shared Narratives: Arts, Culture, and Conflict in Latin America and the Caribbean” for their sixth annual conference at Perry World House.

Penn President Liz Magill gave opening remarks, saying, “This conference exemplifies something wonderful at Penn: the interest and compassion to engage in conversation across disciplines.”

Whether expressed through music, poetry, or streaming on video, stories are about connection, conveying “something unique about individuals, their homes, their languages, their cultures,” said Magill. “They can connect us to something universal ... no matter where or when we’re coming from.”

The conference discussed artistic expression in many forms and included presentations on social change and socioeconomic impact, cultural expression and preservation in education spaces, and repression and resilience in art, as well as a panel on Afro-Latin American and Afro-Caribbean agency, resistance, and power.

The conference was originally convened in order to gather experts on Latin America from all disciplines. In addition to professors from across the University, undergraduate and graduate students also shared their scholarship. Maya Pratt-Freedman, a fourth-year student from San Diego studying sociology and cinema and media studies, played a short clip from her documentary “Essentially Criminal.” Pratt-Freedman took a semester off last year to explore criminalized immigration along the United States/Mexico border.

In a panel on Afro-Latin American and Afro-Caribbean agency, resistance, and power moderated by Odette Casamayor-Cisneros, associate professor of Spanish, three graduate students presented on their research. Bonnie Maldonaldo of Africana Studies spoke on “Armas y Comida Pa’l Pueblo: Food as Resistance in the Dominican Nation.” Alexandra Sánchez Rolón, also of Africana Studies, discussed “Bomba Music and Resistance,” while Joao Nery Fiocchi Rodrigues in sociology presented on narrations of slavery and state formation in the Americas.

In the keynote address, “Playing Boring Games, Building Cross-Border Cooperation,” Juan Llamas-Rodriguez of the Annenberg School for Communication imagined the border as a board game. He created a playable game where the object is to repair all the sewers in the border region, a goal that can only be accomplished if all the players work together.

The limited funds available in the game and the restrictions placed on players’ mobility across the border are two of the main impediments to achieving the game goal before it is too late, said Llamas-Rodriguez. These features are research-based logistical hurdles that are inherited from not cooperating across borders, he said.

Game playing can be an agent for social change, Llamas-Rodriguez said. In his game, players are meant to ask critical questions, like “Why are the stories being told in a game? Why do the characters look the way they do? Why are the players rewarded for certain actions and punished for other actions?” Reflective play can be a catalyst for transformative possibilities as players examine their own actions within a social context, he said.

“The need for a bottom-up approach is critical in border regions,” said Llamas-Rodriguez. “The problem I think lies in the current dispositions that prevent these policies from moving forward: entrenchment, antagonism, apathy. As long as we see the border region from the perspective of the nation state, we will remain uninterested in protecting the livelihoods of border residents.” The answer is to move from a static position protecting the state towards regional cooperation, he said.

The “boring” adjective in the title was actual feedback that Llamas-Rodriguez received when he submitted his game when he sent the game into a peer-reviewed journal. Boring, he said, is part of the point.

“We’re ignoring so many of these border issues because these aren’t the flashy issues; this isn’t the exciting part,” Llamas-Rodriguez said.

Llamas-Rodriguez suggested that this game could be played by different agents before meetings about border issues as a way to get people talking and collaborating together. Until people are willing to engage in “boring” policy issues and take the time to fix them, nothing is solved, he said.

This year's conference was organized and chaired by Mércia Flannery, senior lecturer and director of the Portuguese Language Program (Chair), along with faculty and staff from across the university, including representatives from the Center for Latin American and Latinx Studies, School of Nursing, School of Social Policy and Practice, La Casa Latina, and Penn Global. The conference was largely funded by Penn Global.