In Memoriam: Emile Bruneau, Peace and Conflict Neuroscientist

After nearly two years battling brain cancer, Bruneau passed away on September 30.

Emile Bruneau had a front row seat to many historic global conflicts: He was in South Africa at the end of apartheid. In Ireland during “The Troubles.” In Sri Lanka during a Tamil Tiger attack. Seeing the darkest impulses in humanity – and how similar they seemed across cultures – led him to his life’s work: using the tools of neuroscience and psychology to bring groups of people together with the goal of building lasting peace.

In late 2018, Bruneau returned from a trip to Colombia, where he met with former guerilla rebels from the FARC in an effort to help them integrate back into Colombian society after decades of fighting. He began to notice his computer screen was getting progressively darker. Then the headaches began, and as a neuroscientist, he had an inkling of what it meant.

In the final days of 2018, Bruneau was diagnosed with glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer. Medical averages told Bruneau he had about 14 months left, but nothing about his reaction to the diagnosis was average.

With a peaceful and radiant optimism that was his signature, he embraced this challenge as an opportunity to thoughtfully design the time he had left. He was determined to accelerate the timeline of his work, designing scientific interventions to bring peace to people in conflict, just as he was focused on laying the foundation for a strong, resilient future for his wife, Stephanie, and their children, Clara and Atticus.

After 20 months of living life to the fullest each day, Bruneau passed away on September 30 at the age of 47.

Following his diagnosis, Bruneau reached out to several filmmakers to help preserve his story and further his mission. The following 16-minute short film is the first in that collaboration.

Emile Bruneau was born in California at Stanford Hospital in the fall of 1972. Shortly after Emile’s birth, his mother developed schizophrenia, and the challenges of this illness were life-altering — she spent much of the rest of her life struggling with this disease, often experiencing homelessness and reliant on the kindness of strangers. Bruneau was raised by his single father for the first few years of his life, and later by his father and stepmother. His father’s creative and cooperative parenting style nurtured an independent and thoughtful mind, as well as a deep sense of exploration and play. Bruneau remained connected to his mother as he grew up, and the love and compassion between them never faltered. He spoke with gratitude later in life about how his mother had never let her own struggles through darkness negatively affect her son.

Despite what might have been a traumatic situation, Bruneau always spoke of his childhood as idyllic, and credits his mother for inspiring what would become one of his core professional interests: empathy. As he sought to understand his mother’s reality, he developed a strong sense of empathy at an early age, as well as a desire to understand more about the human mind.

Bruneau attended Stanford University where he majored in human biology — a track combining biology with psychology, sociology and anthropology — which was well-suited to his interdisciplinary way of thinking. He competed on the Stanford rugby team, where he was known for both the ferocity of his tackle and the integrity of his sportsmanship.

After graduating, Bruneau volunteered in newly post-apartheid South Africa and then spent the next seven years in the Bay Area, teaching high school science and, later, PE at the Peninsula School, the progressive elementary school he had attended in his youth. He also coached the Stanford women’s rugby team, earned a black belt in karate, and rebuilt a 1929 Ford Model A which he later drove across the country with his father.

On one of his summer breaks, Bruneau volunteered at a conflict resolution-focused camp for Catholic and Protestant boys in “The Troubles”-era Ireland. After three weeks of seeming success, where friendships formed between boys from both groups, it all came crashing down on the last day when an all-out brawl broke out, split along religious lines. Bruneau realized then that conflict resolution strategies were typically devised on instinct, without any scientific evidence as to what actually works. That recognition sparked his research interest into learning which strategies might be effective in building lasting peace.

On a different break from teaching, he traveled to visit friends in Sri Lanka. Just hours after his arrival, Tamil Tigers bombed the airport where he had flown in. Bruneau spent the next several weeks trailing two journalist friends as they interviewed people on both sides of the conflict.

Having seen groups in conflict all over the globe, Bruneau began to reflect on how the antipathy people have about opposing groups was surprisingly consistent.

With these ideas in the back of his mind, at 29, Bruneau entered a Ph.D. program at the University of Michigan in cellular and molecular neuroscience. While there, his research team discovered that synapses — the connections between nerves and their targets — are incredibly dynamic, driving home to him that at the sub-cellular level, our brains are made to change.

While he loved looking at how brain cells change, Bruneau was drawn more to questions about how minds change, and specifically how to turn conflict into peace. Realizing he would need to learn the tools of human neuroimaging, he approached Rebecca Saxe, Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience at MIT, and over the course of an intense three-hour conversation, talked her into taking him on as a postdoctoral fellow. Focusing on empathy, he used fMRI to study the brains of people on opposite sides of conflicts, such as Israelis and Palestinians or Republicans and Democrats. He began to identify brain regions associated with conflict and how different experimental interventions altered participants’ brain activity.

In 2015, Bruneau moved to the Annenberg School at Penn to become a visiting scholar in Professor Emily Falk’s Communication Neuroscience Lab. He found the discipline of Communication a welcoming one. After a year, he made the move to Philadelphia permanent, becoming a Research Associate and Lecturer at Annenberg and taking on several postdoctoral fellows.

At Annenberg, Bruneau established the Peace and Conflict Neuroscience Lab, whose tagline neatly summarizes Bruneau’s professional mission: “putting science to work for peace.”

“Emile brought so many different groups of people together — scientists, filmmakers, NGOs, everyday people living in conflict — using all of the tools at our disposal to rigorously test what works and why,” says Emily Falk. “He was fully present in every conversation he had, and made everyone on all sides of an issue feel like their voice mattered, even if he didn't agree with them.”

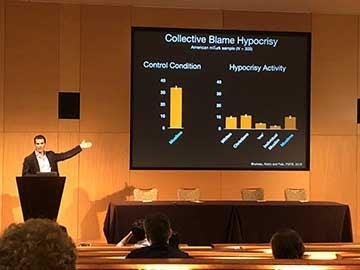

In addition to studying empathy, Bruneau’s research was concerned with meta-perceptions, which concern how someone believes their enemy sees them — beliefs that are often harsher than reality. For example, Bruneau’s recent studies of Democrats and Republicans in America found that both groups wildly overestimate the degree to which the other group dislikes them. He worked on designing interventions that would help opposing groups bridge the imagined gulf between them by understanding that they were not as far apart as they believed.

Bruneau’s lab also studied dehumanization, the degree to which people view outgroups as less than fully human – a strong predictor of violence against them. His work showed that across cultures, people view entire categories of people as subhuman, and are often willing to admit it freely. He then used this information to build interventions to counter it.

The interventions he designed were specific and operational. In a 2012 paper he co-wrote with Rebecca Saxe for the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Bruneau worked with Mexican Americans and White Americans in Arizona, as well as Israelis and Palestinians, and found that when groups of people with less power share their stories and perspectives with someone in an opposing group with more power, both came to like each other more.

“As a scientist, Emile was rigorous, realistic, and humble,” says Saxe. “At the same time, he was a visionary, and he pulled people in with his passion. The research he did perfectly reflected this alchemy: only someone with his gift for relating to human beings could have done these groundbreaking studies.”

Annenberg School Dean John L. Jackson, Jr. describes Bruneau as “the most humane person I have ever met.”

“Emile spoke with such kindness and optimism and hope about the world around him, even as his research forced him to focus on some of most intractable and violent problems that plague us as a people,” says Jackson. “He walked in the world with such self-evident and conspicuous love on his proverbial sleeves. I found him an inspiration.”

Not satisfied to keep his research in the academic sphere, Bruneau built bridges with peacebuilding NGOs to better connect his research with real-world conflicts and the people working to resolve them. In 2016, he joined a United States Institute for Peace delegation of youth leaders from around the globe on a visit to spend two days with the Dalai Lama in India.

He was also the lead scientist for Beyond Conflict, a global non-profit that brings together brain and behavioral scientists with global leaders, practitioners, and communities to create evidence-based tools to reduce conflict and promote dialogue and reconciliation. For a decade, Bruneau was a key partner in bringing science into the practice of conflict resolution and social change.

“Emile was a brilliant scientist whose pioneering research on empathy, dehumanization, and the psychology of polarization, will literally save countless lives and transform the way we think about and address conflict and reconciliation,” says Beyond Conflict Founder and CEO Tim Phillips. “Emile’s passing is not only a profound loss to his family and friends, but to the world.”

Bruneau and his wife Stephanie loved the natural world. In Boston, they ran a small beekeeping business called The Benevolent Bee, selling honey and beeswax products. In their backyard, they have a garden and a chicken coop. Bruneau would nearly always bike the 11 miles to and from the Annenberg School, and always brought his own container to the food trucks to avoid generating trash.

He was a warm and loving father. He built whimsical touches for his children into their home: an elaborate tree house in the backyard, a spare bedroom turned into a “rumpus room” with a cargo net lining the ceiling, a rock climbing wall, and a hideaway nook in the corner of the ceiling.

During the 2018 Women’s March in Philadelphia, a passerby captured a photo of Bruneau sitting in a tree along the Ben Franklin Parkway, holding a homemade sign reading “Respect for All” in a child’s handwriting and cradling Atticus in his lap.

After he passed away, Stephanie Bruneau shared a piece of writing she found on his computer, addressed to her and written just before his first brain surgery in January 2019:

"I just had a thought: I learned in physics that our physical mass never actually touches another — the outer electrons of each repel, giving us the illusion of touch. As a neuroscientist, I learned that our brains don’t really see the world, they just interpret it. So losing my body is not really a loss after all! What I am to you is really a reflection of your own mind. I am, and always was, there, in you."

Bruneau has been buried in a wildflower meadow in West Laurel Hill Cemetery, where the family tended beehives and spent many happy times.

Donations in honor of Emile Bruneau can be made to the Germantown Mutual Aid Fund or the Miquon School’s Financial Aid Fund.