How News Coverage Distorts America’s Leading Causes of Death

A new study shows how media coverage of sensational risks underemphasized chronic illnesses.

Even though they receive minimal healthcare funding, chronic diseases are the leading cause of death in the United States. They account for 70% of deaths in the U.S. annually, with six in ten Americans suffering from at least one chronic condition. However, coverage of this public health crisis is eclipsed by coverage of risks such as homicide and terrorism — incidents that are far more likely to grab readers’ attention.

Calvin Isch, a doctoral student at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania and a member of the Computational Social Science Lab (CSSLab), explored this bias and imbalance in media coverage in a recent paper. Isch found that the outlets covered tended to amplify sensational risks while underrepresenting chronic risks, highlighting a disparity between risks covered by the media and the mortality risks that statistically threaten Americans the most.

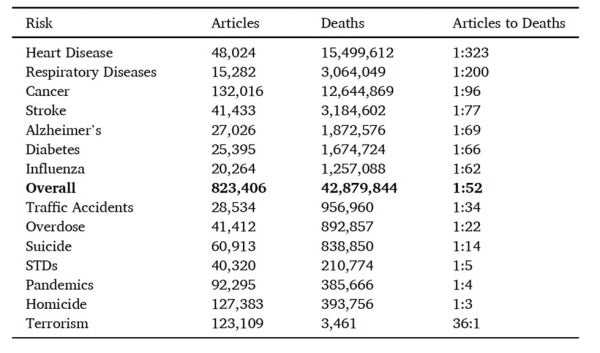

Using natural language processing techniques, Isch collected monthly data on 14 different mortality risks using keyword searches on 823,406 major U.S. news outlet articles that were published between 1999 to 2020.

Heart disease, which accounts for 36% of overall deaths, showed a ratio of one article per 323 deaths; in contrast, terrorism, which accounts for 0.00008% of overall deaths, had a ratio of 36 articles per one death alone, highlighting that deadlier risks received less coverage when compared to their sensational counterparts.

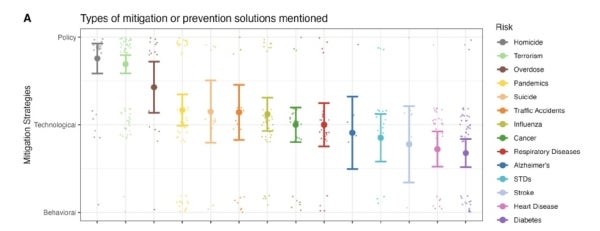

In addition to comparing mortality risks and media coverage, Isch’s analysis looked for mentions concerning health interventions in order to determine if bias manifested in other ways. He found that mitigation strategies fell under three main categories: policy, behavioral, and technological. Articles on chronic diseases usually emphasized changes to individual behavior, while those on sensational risks focused more on collective policy solutions.

The paper also considered the tone of this reporting, showing that sensational risk coverage exhibited more negative emotions when compared to coverage of chronic diseases, which was covered more neutrally in tone.

This data, and the trends it illustrates, provide a useful framework for discussing how health communication can play a role in determining the quality of personal and public health, in addition to barriers such as economic factors. Further exploring the media’s impact on perceptions could help researchers better understand how these perceptions contribute to public attitudes and policy-making.