Giving Voices to the Disenfranchised: Filmmaker, Novelist, Investigative Journalist, and Alumna Nilita Vachani (M.A.C. ’83)

Vachani’s work shares a common thread: giving a voice to the disenfranchised.

Nilita Vachani | Photo Credit: Zayira Ray

After Nilita Vachani graduated from India’s University of Delhi in 1981, her parents gathered enough money for a one-way flight to the U.S., so she could attend the Annenberg School for Communication and pursue her dream of becoming a writer.

But that dream changed once she enrolled in a documentary film workshop, which at the time was taught by well-known anthropologist, filmmaker and musicologist Steven Feld.

“I was completely blown away,” says Vachani (M.A.C. ’83). “In India, documentaries were very dull and boring and propagandistic. The films Steve showed us were incredible. After that, that was it — I wanted to be a filmmaker.”

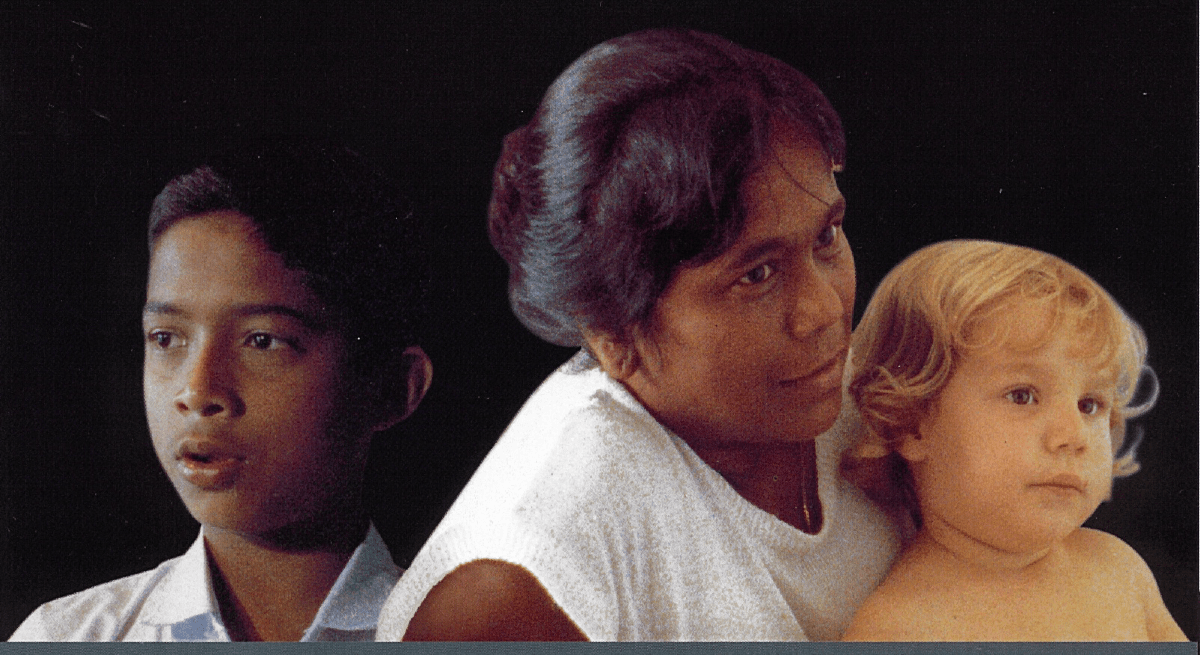

Over the last 30 years, Vachani has produced and directed award-winning documentaries Eyes of Stone, Diamonds in a Vegetable Market, and When Mother Comes Home for Christmas, which take in-depth looks at rural Indian women thought to be possessed; the hand-to-mouth existence of Indian street peddlers; and a poor Sri Lankan mother who left her own children to care for other families abroad.

Vachani achieved her literary aspirations, too, with a debut novel, HomeSpun, about three generations of an Indian family, winning ForeWord magazine’s Choice Prize for Fiction in 2008. Most recently, she added investigative journalist to her resume, with a story about how a West Bengali housekeeper was exploited by a wealthy South Asian family embroiled in the largest insider trading trial in U.S. history. Published last fall in news magazines The Nation and India’s Caravan, the piece was awarded the Asian College of Journalism’s inaugural award for investigative journalism in May.

Regardless of form, Vachani’s work shares a common thread: giving a voice to the disenfranchised. Yet as she sips an iced coffee at a café near New York University, where she’s taught at the Tisch School of the Arts for eight years, Vachani points out that her investigative piece is different from anything she’s done before.

“I’ve always seen my role as someone who throws light on a pressing problem,” she says. “I’ve never seen myself as a social activist. But here, I became one because of the huge and instant impact that the story had.”

Readers from all over the world responded to Vachani’s tale of Manju Das, whose employer, Anil Kumar, stole her identity to conceal money that was gained by selling confidential client information to a billionaire hedge fund manager, Raj Rajaratnam, who used that knowledge to make millions in illegal trades.

In 2011, Vachani began attending Rajaratnam’s trial at the Southern District Court of New York. (Rajaratnam was eventually found guilty on charges of fraud and conspiracy.) Kumar, Rajaratnam, and Goel (another insider turned government cooperator like Kumar) had attended the Wharton School at the same time that she was at Annenberg. When Das’s name was mentioned in court, Vachani was puzzled that neither defense nor prosecution lawyers seemed to be interested in investigating the whereabouts of the domestic worker in whose name her employer Kumar had parked millions of his ill-gotten dollars.

“It absolutely did not make sense to me,” says Vachani. "Why wasn’t Manju Das a witness at this trial?”

So she tracked Das to a remote village in India, where she had been sent following her employer’s arrest, after 10 years of working for him in California. It quickly became clear that Das, who was living in poverty, knew nothing about the scandal and had no idea she was a victim of gross identity theft or had several offshore bank accounts opened in her name.

Vachani says she abandoned the idea of making a film about Das, who feared retribution if she spoke out on camera. But the two kept in touch for years, and Das eventually trusted Vachani enough to enable her to tell the story in print. Because so many readers asked how they could help, Vachani set up a crowd-funding account that raised $9,000 for Das and her family. “She wants to set up a little shop where she’ll sell stationery and dry provisions,” says Vachani. “She’s put her 4-year-old granddaughter in an English medium school. It’s really made a huge difference.”

Lisa Henderson, a fellow Annenberg alum (M.A.C. ’83, Ph.D. ’90) and a communications professor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, invited Vachani to her campus earlier this year to talk about the article. She says the audience was fascinated by Vachani’s dogged detective work and masterful storytelling. “Rarely does a documentary filmmaker become a novelist and then a long-form investigative journalist,” says Henderson. “She is among the wisest people I know. I’m pretty sure she can do anything.”

Vachani began her career in features, working as an assistant director and editor for acclaimed director Mira Nair on movies like the Oscar-nominated Salaam Bombay! That experience inspired her to travel alone throughout north India to research what would become Eyes of Stone, which was banned by the Indian government. In 1990, Vachani had to smuggle the documentary out of the country so it could be shown at a film festival in Paris, where it received rave reviews that led to screenings around the world.

“What’s so astonishing is that you’d think all these years later, things would be different in India,” she says. “Still, if documentary filmmakers make films on subjects that the government does not find palatable, it's really hard to get them seen.”

Vachani’s next film, Reborn in Clay, focuses on an initiative that pairs forensic scientists with artists who create faces from the skulls of victims of unnatural deaths, in the hopes that this will help identify them. And now that her teenage children are older, she would like to spend more time on projects in India. “I’m more interested in doing work that makes a difference,” she says. “That’s what’s driving me now.”