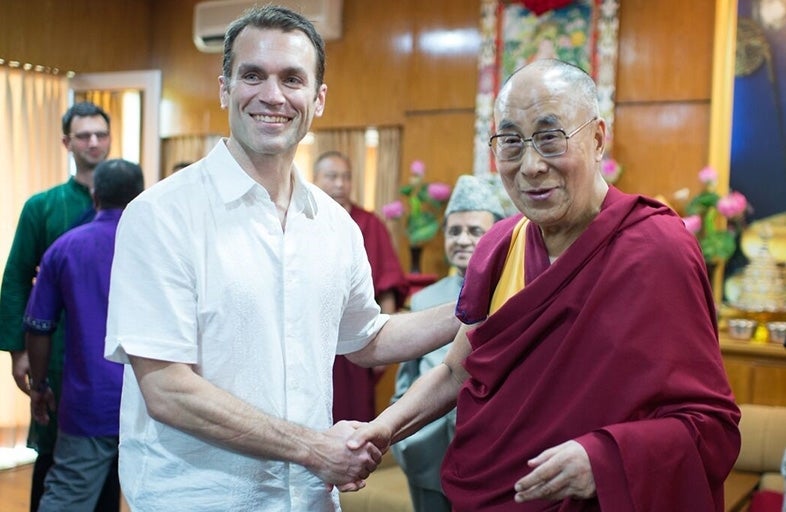

Emile Bruneau Meets With Dalai Lama Through United States Institute for Peace Delegation

Bruneau traveled to India to accompany a United States Institute of Peace delegation of 28 youth activists.

If you could ask the Dalai Lama one question, what would it be?

For most of us, it’s a question about as fanciful as, “What would you do if you won the lottery?” But a few weeks ago, Annenberg Researcher Emile Bruneau was face to face with His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama of Tibet, and given that very opportunity.

Bruneau asked a thoughtful question, rooted in his research on how the brain drives conflict between groups.

“Compassion is the highest goal of Buddhism,” Bruneau began, “but the reality is that when people who have attempted suicide bombings are interviewed later, what characterizes them is not that that they lack empathy, but that their empathy is distributed unequally. They have a lot of empathy for their own group but not for others. My concern is that their empathy can actually be a motivating factor to commit political violence. Is there a concern that if you go halfway in attaining compassion, it could be driving conflict?”

The opportunity to ask this question came as Bruneau was invited to accompany a United States Institute of Peace (USIP) delegation of 28 youth activists ages 18-35 from around the world to meet with the Dalai Lama in Dharmsala, India. The planned four-hour visit last May, aimed at supporting the young leaders in their efforts to combat conflict, stretched into nine as the Dalai Lama was affected and invigorated by the young leaders.

The Dalai Lama’s answer to Bruneau’s question, incidentally, was that Buddhism also values equanimity – removing the differentiation from not only ingroup and outgroup, but between me and you. Decreasing the perception of distinction between individuals has to come along with fostering empathy.

These are all-too-relevant issues for the youth leaders, many of whom have endured unspeakable violence. One had been on a bus in Nigeria when Boko Haram stormed aboard. The young man was put face down on the floor, a gun pointed at his head, when he was saved by the sudden crackle of a radio warning that the military was coming. Another had been a 15-year-old in South Sudan when he found himself at the doorway to a church full of women and children, negotiating with armed militants for the group’s lives. Both men were motivated by those experiences to work for peace.

“These people have experienced the absolute worst things we hear in the news, and they’ve not only overcome it,” says Bruneau, “but used it as motivation to make the world a better place. It’s impossible to overstate how impressive these young leaders are.”

The core theme of the two-day visit to the Dalai Lama’s residence in Dharmsala, the location of the Tibetan government in exile, was pushing past religion to get at the core message of all religions — the universal ethics of peace and love.

The young leaders felt a particular connection to the Dalai Lama, says Bruneau, because he, like many of them, is a refugee. How, they wanted to know, does he maintain both his optimism and his compassion for the Chinese as occupiers?

“He has such a clear message: hate the sin, love the sinners,” says Bruneau, who also praised the Dalai Lama’s disarming style. “Often that day he said, ‘I don’t know the answer to your question. You know better than I.’ It was remarkable to hear that humility coming from a religious leader.”

Bruneau was invited to accompany the delegation as his recent research, some of which was recently written up in the Washington Post, has been on dehumanization and the biases that drive us to conflict, particularly in relation to Muslim refugees in Europe. His research in Hungary found that when Hungarians have high levels of empathy for other Hungarians, they tend to reject and dehumanize refugees. It is only empathy directed at others that turns views more favorable to accepting refugees. Similarly, he has found that dehumanizing rhetoric around Muslims in the United States leads to people advocating things like carpet bombing in the Middle East.

Bruneau also looks at how being dehumanized affects groups, like Muslim Americans. He has found that the more American Muslims feel dehumanized by the rhetoric from Trump and by other Americans, the less cooperative they intend to be with the FBI to help prevent future terror attacks.

His methods draw from cognitive neuroscience to help understand psychological processes like empathy, dehumanization, and motivated reasoning that drive intractable intergroup conflict, like that between the Israelis and Palestinians. His studies use both explicit and implicit measures, and also functional neuroimaging (fMRI).

“To me, Buddhists are the first applied neuroscientists,” he says. “For thousands of years they have been trying to figure out how to tame the human mind. When I think about the group that has made the most headway in systematically getting past our own biases, it is Buddhists.”

On the second day of the program, Bruneau participated in a panel discussion about how to build resilience to violence and trauma. His fellow panelists were young leaders from Morocco and Nigeria, as well as Michael Gerson of the Washington Post and Saji Prelis of the non-profit Search for Common Ground, who helped draft United Nations resolution 2250 to elevate young people into the role of peacemakers.

The group also visited with the Karmapa, the spiritual head of another of the four sects of Tibetan Buddhism. Again, the planned hour visit became two and a half as the young leaders proved so inspirational. The trip also included spending time with Tibetan school children, many of whom have trekked for weeks over glaciers from Tibet as young children, leaving families behind. A student singing performance left an impression on Bruneau.

“The Tibetan style of singing is that the women sing, and they just belt it out — full throated huge delivery of a song,” he says. “To see hear Tibetan refugee girls with strongest voices you can imagine was a perfect symbol of resilience.”