Curator Conversation - “Present Futures: Experiments in Feminist Futurity”

Doctoral students Cienna Davis, Sim Gill, Valentina Proust, Lucila Rozas, and Azsaneé Truss are the co-curators of the art exhibit, “Present Futures: Experiments in Feminist Futurity,” on view now at Annenberg.

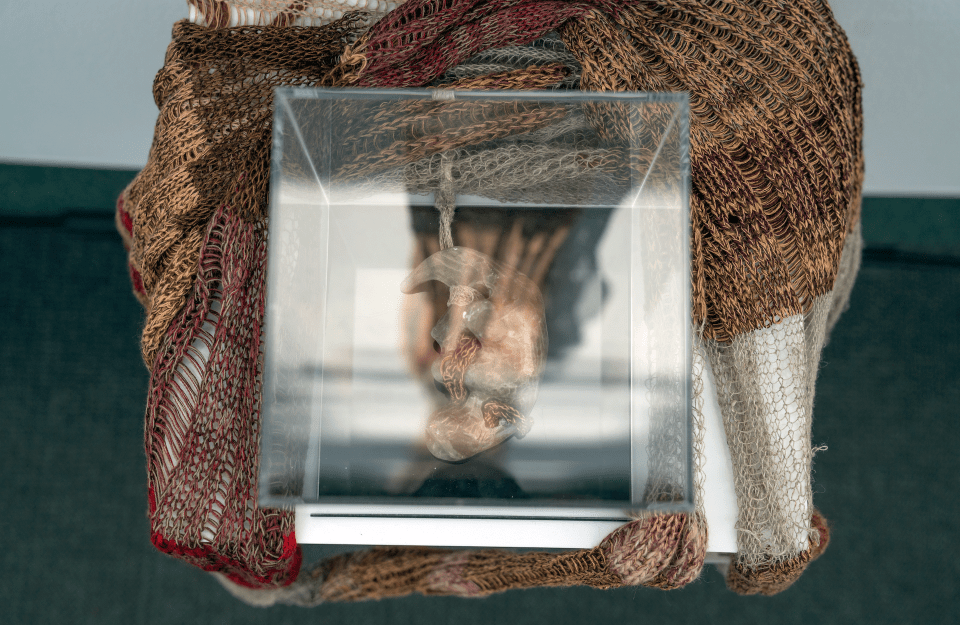

"En la garganta, la pena" by Romina Chuls

On display in the Plaza and the Forum of the Annenberg School until November 19, “Present Futures: Experiments in Feminist Futurity,” is a contemporary art exhibition envisioning feminist solidarities across space and time, in everyday life, with an outlook towards “the future we want to see, right now, in the present.”

The exhibit's curatorial team is made up of Annenberg doctoral students Cienna Davis, Sim Gill, Valentina Proust, Lucila Rozas, and Azsaneé Truss, who all have contributed artwork to the show.

Below, the co-curators answer questions about the exhibition, which opened in conjunction with the two-day Transnational Feminist Networks Symposium in September.

Why did you decide to organize this exhibition?

Davis: Lucila, Azsaneé, and I bonded over our shared interest in multimodal scholarship, having taken ethnographic filmmaking and performance classes together through the Center for Experimental Ethnography. After attending an art exhibition "Partage," organized by a working group of Penn Anthropology Ph.D. students, it struck me that with funding, we could do the same at Annenberg to showcase the value of creative forms and multimodality to knowledge production and create a platform to demonstrate how our creative practices intersect with our research. So when Lucila and I began brainstorming for the Transnational Feminist Networks Symposium, we knew we wanted to organize an exhibition too!

Rozas: What moved Cienna and me to organize an art exhibition was that we recognized the importance of giving proper space to forms of knowledge transmission that are rarely considered authoritative in academia and other spaces, especially knowledges from outside of the U.S. and other hegemonic settings. I believe that bringing them to the fore is an essential part of a truly transnational feminist project!

Can you choose one piece from the exhibit and explain why you wanted it to be included?

Truss: One of my favorite pieces in the exhibition is a piece by Romina Chuls, who is a Peruvian interdisciplinary feminist artist and researcher. Her work focuses on problems faced by Latin American womxn in their daily lives, and the piece we chose to exhibit is titled "En la garganta, la pena." It’s a textile piece that incorporates a ceramic fetus, and uses cross-knit looping, a needle-knitting method used by pre-Hispanic Nasca and Paracas cultures. We thought her use of this medium/her engagement in this practice really beautifully reflected how we often need to use the tools/techniques of our “pasts” in the present to imagine new futures. It spoke to the theme, “Present Futures,” and played with time in a way that we found interesting.

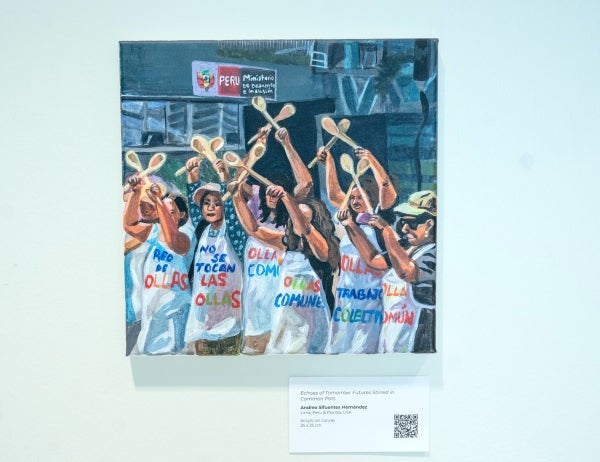

Proust: There are two pieces that, when I saw them during the selection process, not only loved individually but also sparked my interest in how they could complement each other to tell a larger story: "Unpaid Work Starter Pack (Maternal Instinct is the Theory, Domestic Exploitation is the Praxis)" by Yaré Colán and "Echoes of Tomorrow: Futures Stirred in Common Pots" by Andrea Sifuentes Hernandez. Coincidentally, both are by Peruvian artists, but together, they convey a broader narrative about the systemic labor inequities faced by women worldwide and how solidarity can foster networks that inspire visions of a more just and equitable future.

Rozas: Honestly, I love the fact that we were able to honor our multimodal work and give it a space in the exhibition. I am a big fan of Azsanée’s collage, Cienna’s video work, and Sim’s digital painting because I know the thoughtful work that they have been putting into it and how it informs what they are thinking about. As Cienna said, I have witnessed all of these amazing people’s processes in previous classes we took through the Center for Experimental Ethnography and I am always in awe of what they can achieve as artists. And I think their work reflects the theme of the exhibition, as well as the aesthetics we envisioned for it.

However, outside of my peers’ work, one piece that stands out to me is Yare Colán’s "Unpaid Work Starter Pack." I followed her work while in Peru and was thrilled when she responded to our open call. Her piece fits perfectly within the exhibition’s theme, addressing the often invisible labor that women and femmes do to sustain both the present and future of our communities. What resonates with me most is how Yare’s work sheds light on the everyday, gendered technologies we rely on—ones that are frequently overlooked or deemed banal compared to more fetishized technologies like AI, which often carry masculine and racially biased undertones. Her work brings attention to these overlooked tools of labor, making us reconsider the value of domestic labor in a broader societal context. Including her piece not only adds to the thematic depth of the exhibit but also challenges us to question which technologies we uplift and why.

Davis: I designed the graphics for the symposium with the two hands reaching for each other because I have been thinking about modes of connection beyond the social media platforms and digital technologies where so much of our social, emotional, intellectual, and romantic lives revolve. So I was immediately taken by Okyoung Noh’s short film "I Take Care of You and (We) Survive." Her work maps the violence and resistance of displaced female migrants from Asia, with the film focusing on the narratives of body, beauty, and care workers now in the U.S. We see moving images of the artist massaging a performer's body interwoven with videos of other workers’ hands whom the artist has interviewed about their migration and labor experience. The film places visual emphasis on the hands and touch as a mode of offering (& selling) care that can be healing but also contentious. I thought it beautifully aligned with the aspirations of the exhibition to consider the tools available to us in the present to construct alternative futures - with touch being a distinct avenue towards caring, intimate relations.

What is one thing about curating this exhibit that will stay with you?

Proust: Based on the amazing response to our call for artists (with over 60 submissions!), it is clear that there is a strong interest in engaging with these multimodal spaces to discuss such relevant topics. As a co-curator, part of the challenge was selecting pieces that, together, would not only complement each other aesthetically but also create a cohesive narrative around the theme, telling a story. What will stick with me is the process of crafting this balance, bringing together all these different voices and perspectives in a way that not only generates conversations among the visitors of the exhibition but also deepens our collective understanding of the theme (and I think we were able to do this successfully!).

Gill: Curating an art exhibition is no small feat, and until my involvement in this symposium, I had never had the opportunity to experience it firsthand. The process was an eye-opening learning curve. For instance, did you know that not all command strips are created equal? I also discovered the importance of a tool called a leveler—relying on your own judgment for what is a 180 degree angle doesn’t quite cut it in the professional space! Yet, what sticks most with me is that we actually made this happen. That is no small accomplishment! On the contrary, it’s a monumental achievement that breathed life into the exhibition’s theme: "Present Futures: Experiments in Feminist Futurity." And this was definitely our experiment and one I’m so proud to have been a part of!

Rozas: I want to highlight the joy and the privilege of working with such a capacious team to curate an exhibition like this! I think the collective effort made it possible to develop the concept, pick the artwork, and mount the exhibition on time, an outstanding achievement considering this was the first experience most of us had in doing so! I am profoundly grateful to all of the team because they have been amazing at solving all of the challenges that came up during the installation process!

Davis: I will always remember receiving Yaré Colán’s "Unpaid Worker Starter Kit" in the mail from Peru and realizing that we would not only have to find an appropriate mounting device but also use needle and thread to sew into the pieces. Ironically, it required us to all perform different forms of domestic labor to install the piece, which brought into clearer relief the undervalued forms of feminized labor that sustain households around the world.

Describe the piece you contributed to the exhibit and what inspired you to create it

Truss: The two pieces I contributed to the exhibition are collages titled "Transmitting Tresses" (2024) and "Technologies of Motherhood" (2024). "Transmitting Tresses" was directly inspired by Cienna’s dissertation work and her new short film "Digit(al) Dread" that was screened at the symposium. It explores how Black women’s hair practices build networks and communicate in a shared language of care. "Technologies of Motherhood" was intended to trouble our definition of “technology,” which is also a significant thread in Cienna’s work, drawing on scholars such as Armond R. Towns who re-historicize what we consider “media” and “technology.” In this vein, I wanted to consider the often overlooked technical processes, methods, tools, techniques, and knowledges applied in motherhood.

Gill: The piece I contributed to this exhibit, titled "4 Seasons," features four distinct portrayals of experiences: fear, hope, freedom, and silence. I refer to them as seasons because, throughout my research, I find myself cycling through these emotional and experiential states. Sometimes, they overlap, and other times, they flow sequentially, much like the changing seasons. In many ways, this piece mirrors my emotional rhythm of my scholarly inquiry—oscillating between chaos and clarity, challenge and growth—capturing the complexity of academic life and my feminist practice.

Rozas: I created "Geografía de un cuerpo / Las flores reverdeciendo" during a class on performance ethnography at the Center for Experimental Ethnography. It was deeply influenced by Latin American queer performance artists and thinkers Pedro Lemebel and Giuseppe Campuzano, whose embodied practices resist state violence, as well as by feminist protest performances of mourning in Peru, Argentina, and Chile. For me, this piece explores grief and mourning as non-linear, collective processes where memory is continuously activated. These acts, public and everyday, resist the imposed narratives of those in power, who often seek to silence the dead and obscure the truth. This work also carries personal significance, as it allowed me to process the political violence in Peru (my home country), where 50 protestors were killed last year while demanding justice against a repressive regime. By connecting personal grief with collective mourning, I aim to challenge the immobilization of these emotions, showing how they can become acts of resistance and remembrance.

Davis: In response to a world increasingly mediated by digital technology, my collaborative short film "(Digit)al Dread" offers an alternative reading of the "digital" rooted in physical digits - or fingers- and the intimate practices of touch within Black femme haircare and styling technologies. Through street interviews, a hair workshop and focus group, and a durational filming practice in Berlin, Germany, the film examines the tactile and textural networks capable of interlocking diasporic subjects into relations of interdependency, communication, and care. While technological innovation in the Western imagination is dominated by notions of speed, convenience, and efficiency, monetizing social relations and lauding posthumanist futures, the film asks what alternative futures can we envision when we prioritize the slowness, interconnection, and intergenerational knowledge transmission of Indigenous technologies? How might a (digit)al dread disrupt dreadful technological futures?

What do you hope visitors come away with after viewing this exhibit?

Truss: I recently had a conversation with someone who said if they had to pick one word to describe the exhibition, they would choose the word “power.” I thought that was really cool. We tried to curate an exhibition that imagined new futures through a transnational feminist lens, and I think the futures we’re all imagining are those where women and gender non-conforming folks are liberated and able to own and share power in more communal ways.

Gill: As five scholars who embody feminist principles in both our research and personal lives, curating this exhibit provided a unique opportunity to foreground art as a powerful medium for dialogue and a site for reimagining belonging within academic spaces. Despite the inevitable logistical hurdles and occasional shipping chaos, our ambitious vision stands as a testament to the fact that the future is not some far-off ideal, but something we are actively shaping in the present. The works on display—ranging from the embodied labor of care, whether emotional, physical, or financial, to the feminist library and altar—offer a layered exploration of feminist praxis. These pieces, exhibited until the end of November and archived through photographs, conversations, and the relationships forged during the process, will serve as a lasting reminder of our commitment to transnational feminist solidarities. I hope people continue to resonate with these ideas and affirm our ongoing capacity to reflect, act, and ultimately transform.

Rozas: For me, one of the most important things about the exhibition is that it showcases, in different ways, different visions of what enacting the present in the future means and how there are connecting threads in the forms we think about it, which is what, ultimately, allows a feminist transnational project to flourish!

Davis: We often hand over our hopes for the future to those who appear to have power - whether it be politicians or Big Tech corporations that promise to lead the way of human evolution. Futurism is often associated with metal hardware, speed, and convenience of digital networks. I hope the exhibition makes people reflect on alternative futures grounded in the needs/demands of the everyday, in the power of people to forge their visions, in the practices of our grandmothers and great-grandmothers who survived unimaginable circumstances, in the possibilities and creativity of the people around us to forge pathways towards more equitable and sustainable futures. Additionally, I hope it encourages other grad students who to consider the benefit of their artistic practices to their scholarship and to know there is space for this kind of work to be received at Annenberg.

How can art exhibits enhance or expand the “typical” academic symposium?

Proust: I think they can encourage deeper engagements with the topics that are being discussed at a symposium. During a traditional symposium, you listen, take notes, and perhaps ask questions, but the exhibition offers a space and time for contemplation and reflection that a talk cannot provide. It invites the participants to engage with the messages using all their senses, offering a more embodied experience. Art exhibits are not merely complements to a symposium; they have their own identity and role, aiming to generate similar discussions, but through different modalities, making participants active in the creation of meanings.

Truss: I think this exhibition speaks to the importance of multimodal scholarship, which offers people different (and sometimes more accessible) entry points into intellectual conversations. One of the key concepts behind multimodality is the idea that we make meaning in a variety of ways, and for some people, a video or a painting or a collage might communicate in a way that speaks more directly to how they understand the world. Art and media are often able to present ideas and resonate with people in ways that written words or spoken language can’t.

Rozas: I don’t see an exhibition as an extension of an academic symposium but an equally important setting in which knowledge transfer is happening, although slightly differently. I think that there are important processes that art activates at a sensorial level, and helps directly understand and make some ideas and feelings of our own. Our bodies are capable of witnessing, reacting, participating, and engaging with artwork that speaks to us. I think this is central to feminism because it (hopefully) eliminates the distance between the one “doing the speaking” (which is, often, an act of power) and the one listening. This may sometimes get lost in more conceptual artwork that is featured in galleries and museums as institutions that provide authority to the artist. However, I want to think that with our exhibition, we strive to challenge these dynamics and effectively shorten that distance. I believe that it was definitely among one of our goals to make it a space in which these ethics of horizontality are put into practice.

How does your own artistic practice inform your scholarship?

Truss: My artistic practice is basically inseparable from my scholarship at this point. At times, what I’m reading has inspired a piece of art, and sometimes I use my art practice to make sense of new academic concepts or ideas I have. I consider myself a “thinking artist,” which I think implies an artist who thinks in scholarly ways, a scholar who sees thinking as an art, someone whose artistic work is scholarship, etc.

Gill: My artwork keeps me grounded amidst the demands of my scholarship. The subjects I study, and the papers I write are infused with emotions that words alone cannot fully express. And yet, I am deeply passionate about the topics I explore and the conversations I have with fellow scholars; I couldn’t imagine writing about anything else with the same level of conviction. At the same time, I am acutely aware that my research deals with profoundly unsettling and violent histories—stories that are not mine, but inevitably become mine through the act of reading, analyzing, and conducting interviews. Without my art, my scholarship would feel incomplete. It provides a way to communicate the full spectrum of my research—beyond words—capturing the complexities of womanhood, safety, and violence in ways that academic writing alone cannot. It is, in essence, a crucial extension of my intellectual work, giving voice to what language alone cannot and will never be able to convey alone.

Rozas: I also think that, in my case, it is difficult to separate my developing artistic practice from my scholarship. Even though they involve other processes and languages, I don’t think I can conceive them as two different things. When I am reading and thinking with others, my feelings are actively engaged all of the time and I can envision how they can communicate this internal world that I am creating as I am making connections between authors, ideas, and experiences. I do not often know how things are going to turn out in the end when I create art but once I see the final product, for example, after editing a video, I become aware of these worlds and I can more clearly see where I am going with my writing and my thinking. And vice-versa. Sometimes also writing activates in me the need to do something else because I don’t think this language can contain the internal worlds I am making as I read and do research.