“The Communication Research Experience” Tested How to Get Out the Vote for the Midterm Elections

Students conducted an experiment that tested competition and identity priming as possibilities for increasing voter turnout.

Penn students are no strangers to research — they read it, discuss it, and cite it in just about every course. But what does it take — soup to nuts — to actually conduct a research study in Communication?

This semester, a group of six undergraduates found out, as they also tackled an important and timely research question: could they find a way to increase voter turnout for the U.S. midterm elections, an event which took place just 10 weeks into the course?

Partnering with the student group Penn Leads the Vote and the Netter Center for Community Partnerships, the students designed and ran an experiment that tested competition and identity priming as two possible ways to increase voter turnout — with some positive findings.

Understanding how to design and execute research stands to be very useful in the students’ future careers, says Professor Emily Falk, who taught COMM 310: The Communication Research Experience.

“Many of our students want to work for companies where they’ll be trying to change people’s behavior, and in those situations there’s a lot of money on the line,” says Falk. “Regardless of whether they go into finance or marketing or work for an NGO, it's an important and valuable skill to be able to figure out whether A causes B — whether something you do has some actual effect on the outcome, or whether it’s simply a correlation that would have happened even if you hadn't spent any money.”

“The Sprint”

“Cramming an entire experiment into a semester is a sprint,” says Falk, who noted that the fast approval of revisions — in one day! — from Penn’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) as the class worked was essential in making the experiment happen.

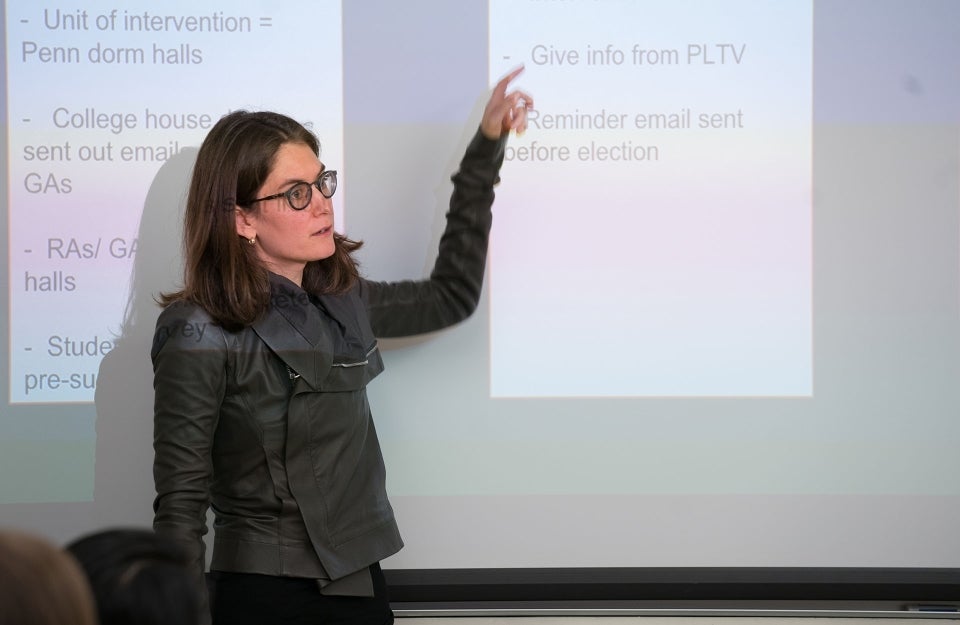

After zeroing in on voter turnout as their focus, the students began by reviewing literature to see what types of interventions have been successful in changing all different types of behavior.

Student Courtney Quinn (C’19) brought up her experience on the Penn volleyball team, and how team goals had gotten her and her teammates to participate in activities.

“At a very primal level, competition determines which species survive when they compete over limited resources,” explains Daniella Wirtschafter (C’20). “Research has shown that [competition] has led to increased motivation and increased performance, so we wanted to see how competition can be translated to increase voter registration and voter turnout.”

The students also zeroed in on identity priming, which included either reflecting on what made them unique (individual identity priming) or why their identity as a Penn student was important to them (group identity priming).

“The identities we choose to associate with change the ways we move through the world,” says Hadeel Saab (C’20). “This is evident with religion, politics, occupation, and gender. It affects the consumer products that we buy, the music we listen to, and all of our daily activities.”

After zeroing in on competition and identity priming, the students designed an experimental methodology and consulted with numerous political scientists and political communication experts on campus, including Dean Michael Delli Carpini, Marc Meredith, Dan Hopkins, Diana Mutz, and Yphtach Lelkes, as well as Cory Bowman from the Netter Center.

The Experiment

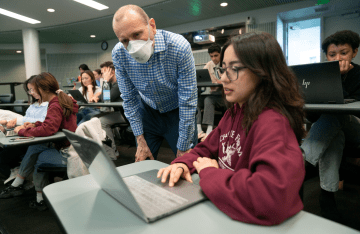

Working with the college house deans, the students found 22 different halls willing to participate, and these halls were randomly assigned to one of seven conditions.

After taking a baseline survey online and completing consent paperwork, the students attended a pizza party on their hall, where they all received voter information from Penn Leads the Vote.

While the control condition only got basic information about voting, in the other six groups, students from COMM 310 also used a script to lead the students through priming and/or competition exercises.

The priming activity involved writing a short paragraph. It tested either individual priming — what makes each person unique — or group priming — the identity that comes from being part of the Penn community, compared to a control (no priming) condition.

Meanwhile, the competition groups were told that the experimenters would publish either a list of how many people on each hall voted (group competition) or the names of the individuals who voted (individual competition).

All the students later received a follow-up reminder to vote that reinforced their competition or identity conditions.

After the election, another emailed survey asked whether the students voted, and included additional questions.

The Results

On the 22 halls that participated, a total of 179 students completed the initial survey, and 136 of those also completed the post-vote survey. Seventy-six percent of the students reported that they voted on election day. (These results will be confirmed once objective voter logs are available.) Roughly half of students vote during the presidential election years, with much lower voting rates during a typical midterm year.

The students found that priming people’s identity significantly increased self-reported voter turnout, and was particularly successful for the students who identified as liberal.

While the students did find that competition generally increased voter turnout, their analysis revealed that the differences were not statistically significant from the control group.

There are many reasons why data that appears to show a trend may not hold up under statistical scrutiny. For example, the number of participants in a study may be too low, the data may vary enough that drawing a conclusive finding is difficult, or there may not be a real effect. Learning to determine when a finding is valid is an important skill taught by the course.

Next semester, Hadeel Saab and Anna Waldzinska (C’20) will be continuing on as research assistants in Falk’s Communication Neuroscience Lab. Falk's team will delve further into the data and continue on with the research in communication with the students from the class who are interested in continued participation. Falk also hopes to replicate the study in COMM 310 next fall during the 2019 local elections.

Regardless of the significance of their findings, the students learned a lot about the power of research to help society.

“Our experiment wasn’t a traditional intervention like handing out flyers or knocking on doors,” says Waldzinska. “If I was going to advise Penn Leads the Vote, I would say try out different quirky and creative ways to get people to vote. Especially with young people, different methods like competition and priming could definitely work.”