Communication Majors Get Hands-On, Quantitative Research Experience in New Course

This kind of course on study design and statistical methods often isn't taught until graduate school.

José Carreras-Tartak

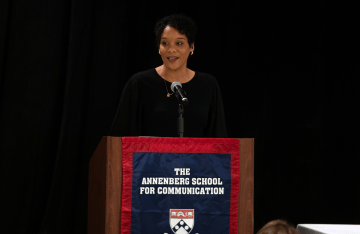

What characterizes effective messaging campaigns? What makes some people more likely to share ideas? How would we know if a campaign is working? This semester, Professor Emily Falk offered a new undergraduate course to arm an emerging generation of researchers with the skills to conduct rigorous quantitative research that would allow them to answer these questions and a wide range of others.

While Communication majors read, analyze, and conduct research in other courses, the hands-on dimensions of study design and statistical methods needed to do the kind of research Falk pursues in her own Communication Neuroscience Lab often isn’t taught until graduate school. But after receiving numerous requests from undergraduates for more hands-on experience doing quantitative research, Falk designed COMM 310: The Communication Research Experience, offered for the first time this past semester.

“It’s one thing to read and write about research that’s already been done,” José Carreras-Tartak C’19 said, “but it’s an entirely different experience to actually be able to do the research yourself.”

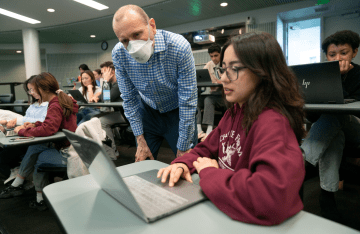

The enrollment was just four students, giving Falk and her teaching assistants — Annenberg doctoral students Elisa Baek and Rui Pei — the opportunity to work in depth with each student on their own Communication research project.

“Part of this course was about training the next generation of scientists,” Falk said. “We did a lot of professional development around working with collaborators, learning to structure a research project, and how to actually execute it. The students also spent some time in my lab, observing our work.”

In her 17-member lab, Falk, who has received numerous awards for being a rising young star in her field, blends Communication, Neuroscience, and Psychology to study issues of how the brain processes messages, and how those mechanisms in the brain drive human behavior.

For her students, Falk chose research projects that were big enough they mattered but small enough that the full research experience could fit into a single semester. By selecting research topics that she and her lab were already exploring, the students were able to be involved in advanced work by partnering closely with Baek and Pei. Falk also pulled in her lab’s research coordinator, Ally Paul, and others from the lab to work with the students.

"I really enjoyed how self-led the course was, as we were each paired with a graduate student who could provide us with individualized guidance," said Nick Joyner C'19. "This was helpful in allowing us to tailor the course and the research we pursued to match our specific interests and abilities."

Throughout the semester, Falk guided the students through the research process; they learned about how to choose a question they cared about, how to derive hypotheses based on prior scientific work, hypothesis pre-registration, computer programming, data analysis and interpretation, and open science practices. Falk invited seven graduate students and postdoctoral fellows to speak about their own research to the class, and organized a panel of scholars to talk about what it’s like to go to graduate school.

After a semester of working on their research projects, which included periodic updates to the class, the students presented their findings as a final project:

- Jacob Gursky C’19 researched social network structures and adolescent risk taking, looking for a link between risk taking and expanding one’s horizons socially.

- Carreras-Tartak analyzed teens’ responses to anti-smoking messages, hoping to determine how to make targeted ads more effective for different types of teens.

- Joyner studied which teens share and receive news online and considered whether someone’s social value orientation influences how much news they share and how they share it.

- Kamilla Yunusova C’18 tested a new health app aimed at increasing physical activity in adults.

Some of what the students expected to find was supported, and some was not, but Falk wasn’t surprised. As she says, “That’s how research works—if we knew the answer beforehand, we wouldn’t have to do the research.” Often, researchers are wrong about what they expect to find, or they discover that there’s just no significant relationship at all. Most importantly, the students now have the skills to approach a variety of research questions moving ahead.

“I was really pleased with their work,” said Falk. “The students were in this course for the experience of research and to try to learn new things. They were bright and motivated, and I was really impressed.”

In fact, Falk says she and her lab plan to follow up on some of the research the students conducted this semester, describing their projects as “inspiring.” In addition, Yunusova is enrolled in an Independent Study course with Falk next semester to continue developing the health app.

“This class was an incredible microcosm of what it’s like to be a graduate student doing research,” said Gursky. “I learned things I didn’t know I needed to know about turning research into a viable paper. I would recommend COMM 310 to anyone even remotely considering a career in research.”

Falk admits that the world of communication research is vast, and this first run of the course only offered students one flavor — specifically quantitative research in the field of communication neuroscience. She imagines eventually being able to expand the course to offer students hands-on research in more areas of Communication, including both qualitative and quantitative projects.

“I really enjoyed teaching this course,” Falk said. “The atmosphere was like the students were part of our lab. I’d love to teach the course again if more students are interested in this kind of hybrid classroom-lab experience.”