Collaborating to Advance Health Communication

As a generation of pioneering scholars retired, several new hires are working together to continue Annenberg’s legacy as a leader in Health Communication.

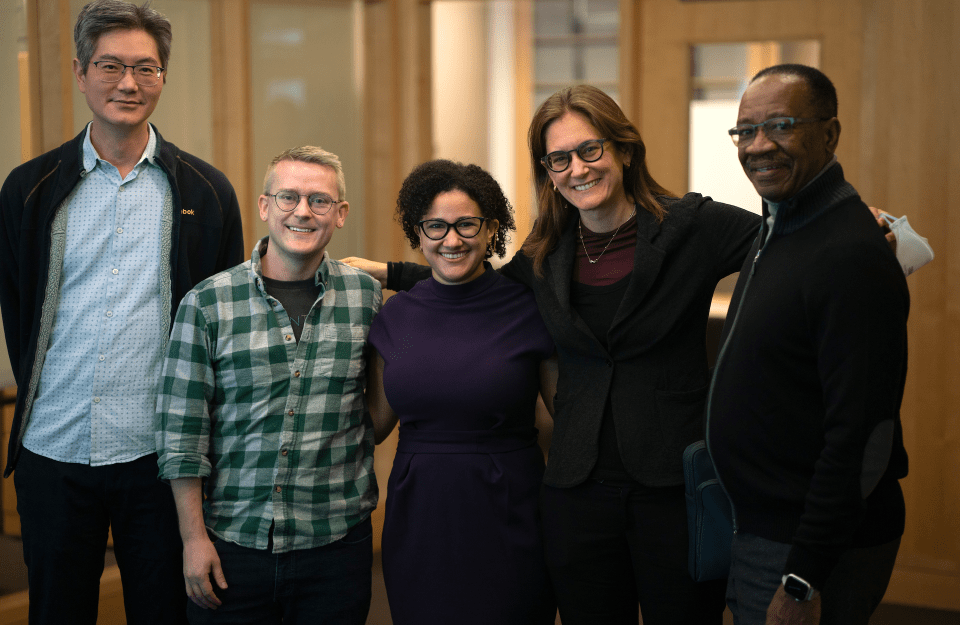

Mary Andrews (center) successfully defended her dissertation in December. Her dissertation committee members included four health communication faculty (L to R): Andy Tan, David Lydon-Staley, Emily Falk, and John B. Jemmott III.

What goes on in people's brains when they feel the urge to smoke? How can public health officials prevent young people from starting to vape? What drives people to believe in health-related conspiracy theories?

These are just some of the questions that Annenberg School for Communication Professors David Lydon-Staley and Andy Tan are helping one another answer.

The two health communication researchers both joined the Annenberg faculty in 2020, working from home as the COVID pandemic was limiting social contact — and urgently demonstrating the importance of their work.

Now with offices on the same floor, they make use of one another’s strengths while carrying out research — Tan is Lydon-Staley’s go-to source for everything community-related and Lydon-Staley is Tan’s touchstone when thinking about longitudinal data.

They, along with fellow faculty members Emily Falk, Dolores Albarracín, John Jemmott III, Kathleen Hall Jamieson, Damon Centola, and others are keeping the School at the cutting edge of health communication research, a legacy established by long-time collaborators Professors Emeritus Robert Hornik and Joseph Cappella, now legends in the field of health communication, and others like the late Martin Fishbein.

This semester, they began meeting as a more formal health communication group with an eye to increasing their collaboration and impact.

Together Tan and Lydon-Staley search for ways to curb tobacco use and promote health and well-being, especially in young people, though each approaches this goal differently. Much of Tan’s work involves community-engaged research, bringing in community members to co-create with academics, while Lydon-Staley asks participants to answer questions on their smartphones as they go about their daily lives, looking at health-related decisions made in everyday contexts.

Cappella and Hornik are their ideal model for academic collaboration.

“We refer to Bob and Joe's work all the time,” Tan says. “I might think, ‘Oh well, this is a novel idea,’ and then I realize that they already covered that 13 years ago.”

Tan and Lydon-Staley are currently collaborating on two projects: one involves creating and testing public health messages designed to educate smokers about health harms of nicotine and the other analyzes how people search for health information online.

Getting Curious

Lydon-Staley has been researching curiosity for years, mapping what people feel and what people do when their interest is piqued.

“If you're curious about a piece of information, you're more likely to remember it,” he says.

He and Tan are using this fact to craft educational messages about nicotine that elicit curiosity and better recall in smokers. These messages are aimed at groups traditionally targeted by tobacco advertisers — young adult smokers, rural adult smokers, and Black smokers.

“More recently, public health experts are trying to communicate that there is a continuum of harm when it comes to tobacco products,” Tan says. “At the top you have a cigarette and then on the lower end, you have products like nicotine patches. If someone is smoking, we want them to stop, or at least use something on the low end.”

Communicating that continuum is tricky, Tan says, but crucial, especially as the FDA moves toward establishing low-nicotine cigarettes and vapes.

“We want to have a head start on understanding how nicotine messaging should be presented to specific groups of people in order to have positive public health impacts and not lead to unintended consequences,” Tan says. “We don’t want people who aren’t using tobacco to start smoking.”

Their early data is providing insight on which curiosity-eliciting techniques work for which groups of people, and will lead further efforts to tailor effective messages.

“Exposure to information is just one part of communication, people need to remember what they've been exposed to.” Lydon-Staley says.

Finding Health Information Online

The pair’s other ongoing project analyzes what happens when people turn to the internet for information about health. If they Google, what results turn up first? Which articles do they read? What links do they click?

Curiosity also comes into play here. “One of the questions we are trying to answer is, ’Do you spend longer searching for information if you're more curious to know the answer,” Lydon-Staley says.

During this study, participants are given five health-related questions and up to 20 minutes to search the internet for answers.

“We're basically trying to capture what happens in everyday life when people are looking for answers to their health-related questions online — but it's a bit of a black box because it's very difficult to capture that data in the first place,” Lydon-Staley says. “And then once you have that data, how do you analyze it?”

Tan and Lydon-Staley hope this experiment will lead to better understanding of what types of information-seeking approaches shape people’s perceptions of healthy behaviors, for example, if searching about the flu vaccine will make someone more likely to get vaccinated against the flu.

Future Health Leaders

Lydon-Staley and Tan are not alone in their collaboration efforts at the School. At meetings with their fellow faculty about the future of health communication at Penn and beyond, they discuss their appreciation for their students and efforts to educate the next generation of health communication researchers.

“Annenberg has always been a leader in health communication,” says Vice Dean Emily Falk. “It is extraordinary to see all the ways that our current faculty are imagining new ways to confront society’s most pressing problems and improve people’s health and well being through their scholarship.”

Albarracín, Falk, Jemmott, Lydon-Staley, and Tan are all mentors in the Penn Undergraduate Research Mentoring (PURM) program, which brings undergraduate students into active labs to gain research experience. They often serve together on graduate students’ dissertation committees and work together to help students get published.

“Students here are part of the collaboration between different labs and researchers,” Lydon-Staley says. “My students take Andy’s classes and Emily’s classes and Dolores’s classes and John’s classes and receive diverse perspectives of the field and methods to do research within it. I think that's really powerful.”

Tan agrees.

“We want our graduates to have experience with many approaches to research,” he says. “They may ultimately choose to specialize in one area or the other, but their ability to appreciate the scientific contributions of different approaches, represented by the faculty, can lend themselves to be, ultimately, good researchers, mentors, and teachers themselves.”