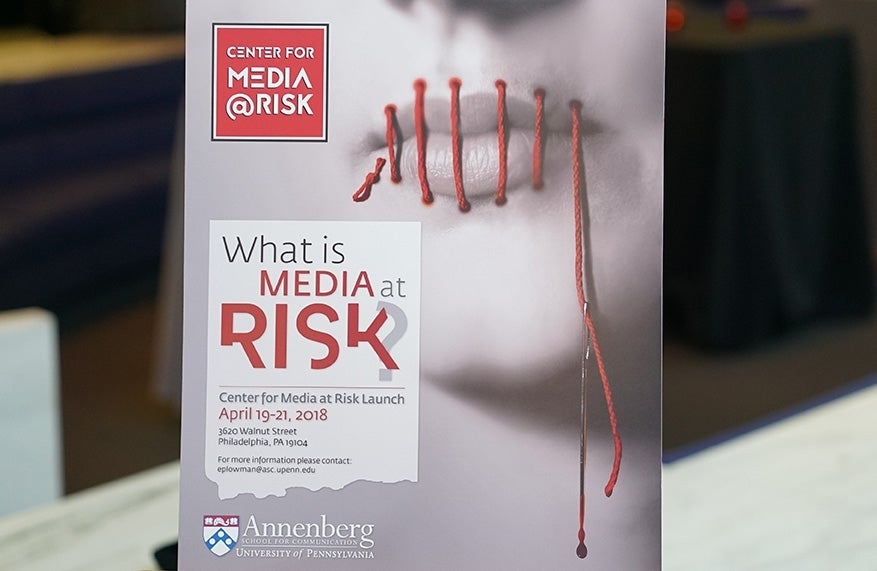

Center for Media at Risk Launches With Symposium “What Is Media At Risk?”

On April 19-21, the Annenberg School celebrated the launch of the Center for Media at Risk.

“Media at risk is the clearest indicator of how bad things can go when democracies start to slide,” began Professor Barbie Zelizer before a crowd of 125 academics, journalists, filmmakers, and writers.

“Yet in many places around the globe,” she continued, “the political intimidation of media practitioners has become the rule, not the exception. Today and tomorrow, we hope to begin strategizing, what that looks like, what it means, how to resist it.”

On April 19 - 21, the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania celebrated the launch of the Center for Media at Risk, a new center to study and counteract the way that practitioners of all forms of media have been harassed, silenced, and coerced by the rising tide of authoritarianism around the globe.

The three-day launch event, “What is Media at Risk?” began on Thursday evening with writer and media critic Soraya Chemaly, who spoke about who defines risk and why it matters.

View a gallery of photos of the event here.

Chemaly described online rape and lynching threats to women writers, and how the public often brushes it off as the digital equivalent of street harassment. Who decides what is dangerous and what is safe?

She showed charts to explain that lack of inclusivity creates a void where knowledge about women and people of color is lacking, and they are seen as less expert.

“We need to look at risk by looking at what is embedded in systems, and thus entrenched and normalized, because these are a part of media ecosystems, culture, and production,” she said. “The question of “What is risk?” is fundamentally tied to why lack of diversity is not considered a risk.”

Zelizer’s introduction on April 20 kicked of a series of four panels that extended from Friday morning through Saturday afternoon, each of which addressed a critical area for media freedom: Digital, Entertainment, Documentary, and Journalism. The panels began with 10-minute presentations, followed by a lively Q&A with the audience.

The Digital panel spoke to the problems of online misinformation, with platforms like Facebook as the gatekeepers for news.

Maria Ressa, the CEO and Executive Editor of the Jakarta-based news site Rappler, offered her home country as a cautionary tale for journalism under authoritarian leadership. The government, she says, was able to weaponize the news people get from Facebook, which essentially is the internet in the Philippines.

“The propaganda that was there became exponential,” says Ressa. “A lie told a million times is the truth,” she said.

University of North Carolina Associate Professor Zeynep Tufecki also addressed the dangers of the Facebook algorithm as arbiter for the news people see. After watching Trump rallies for research in 2015, she was surprised to see white supremacist videos being suggested to her. She tried an experiment with other topics: running videos led to ultramarathon suggestions, while vegetarian videos prompted vegan suggestions.

“YouTube’s algorithm has figured this out for people: Whatever you’re watching, it will show you something edgier,” said Tufecki.

Author Amy Siskind and Samuel Sinyangwe, co-founder of Mapping Police Violence and Campaign Zero, also spoke about the significance of information that is absent.

Sinyangwe, alarmed by the absence of data on police shootings, created a comprehensive database to track people killed by police in America. He also spoke of using the internet to crowdsource and engage people at scale.

Siskind, who puts out a weekly list of what his changing toward authoritarianism, discussed the importance of writing down facts and events, and keeping our eyes on important news instead of the distracting minutiae of who is in or out of favor with the president.

“The media was obsessed with how much Scott Pruitt was spending on flights, or for his phone booth,” she said of the EPA Chief. “The bigger issue is that he doesn’t believe in climate change.”

The Entertainment panel looked at the barriers to media freedom in Hollywood.

Biola University professor Nancy Wang Yuen was quick to point out that Hollywood is not a democracy, with showrunners having final authority on decisions, and the overwhelming majority are white men. “Important in how we look at how entertainment gets made is who gets to make it,” she said.

Journalist Mo Ryan, who recently stepped down as Variety’s TV critic, described a challenge with the recent boom in the number of scripted television shows, versus a static number of entertainment journalists.

“Imagine for every show, there are 10 publicists,” she said. “There are so many shows and an apparatus of power around each one that’s trying to get the media to say or not say a certain thing.”

The panel also discussed the challenges to the Writers Guild of America as unions remain under attack in the U.S., and the degree to which late night comedians are a form of news.

The Documentary panel explored the ethics and risks of social issue documentary, including getting attention for important subjects while preparing both filmmakers and subjects for a potential backlash from entrenched power structures.

Sam Gregory, program director for WITNESS, illuminated the challenges around how to use bystander-taken footage of crimes — which has become increasingly available thanks to modern phones — and to advise those who may take it in the future on how to make such footage useful in getting justice.

Simon Kilmurry, Executive Director of the International Documentary Association, described how trolls can be used online to systematically discredit filmmakers.

“The power of trolls is not always that the claims they make stick or make sense, but that they sow seeds of doubt that accumulate into impactful campaigns,” said Kilmurry.

Saturday morning’s Journalism panel included NYU Professor Jay Rosen who described the Trump White House’s campaign to discredit the American press — a campaign he notes is proving effective. Rosen particularly laments the erosion of an environment where Americans shared certain basic facts as the pro-Trump third of the electorate pays attention only to the news as dictated by Trump himself, rejecting independent sources on principle. (His talk was adapted into an article in the New York Review of Books, “Why Trump Is Winning and the Press Is Losing.”)

Azerbaijani journalist Arzu Geybulla described the perks like free housing and high salaries that pro-government journalists get in Azerbaijan, while journalists reporting the truth are beaten, blackmailed, harassed, defamed, and arrested on bogus charges.

Parker Higgins, Director of Special Projects at Freedom of the Press Foundation, spoke of tools like SecureDrop to help journalists and sources communicate confidentially, noting that the service began in the Obama years. Protection of journalists isn’t a right or left issue, he said, but rather one of upholding democratic ideals.

George Washington University professor Silvio Waisbord described the threats to journalists as a human rights problem. “Journalism is a canary in a coal mine case for human rights,” he said.

It was a sentiment echoed by Annenberg Dean Michael X. Delli Carpini.

“In the end, it’s not the media we’re concerned about,” Delli Carpini said during the event. “It’s the public we’re concerned about. Ideally we’ll be able to learn some things today that have a practical application in trying to preserve the role the media plays in democratic societies across the globe.”