Groundbreaking Analysis Unveils Secrets to Predicting and Changing Human Behavior

Pandemics, global warming, and rampant gun violence are all clear lessons in the need to move large groups of people to change their behavior. When a crisis hits, researchers, policymakers, health officials, and community leaders need to know how best to encourage people to change en masse and quickly.

But each crisis leads to rehashing the same strategies, even those that have not worked in the past, due to the lack of definitive science on what interventions work across the board, which is often combined with well-intended but erroneous intuitions.

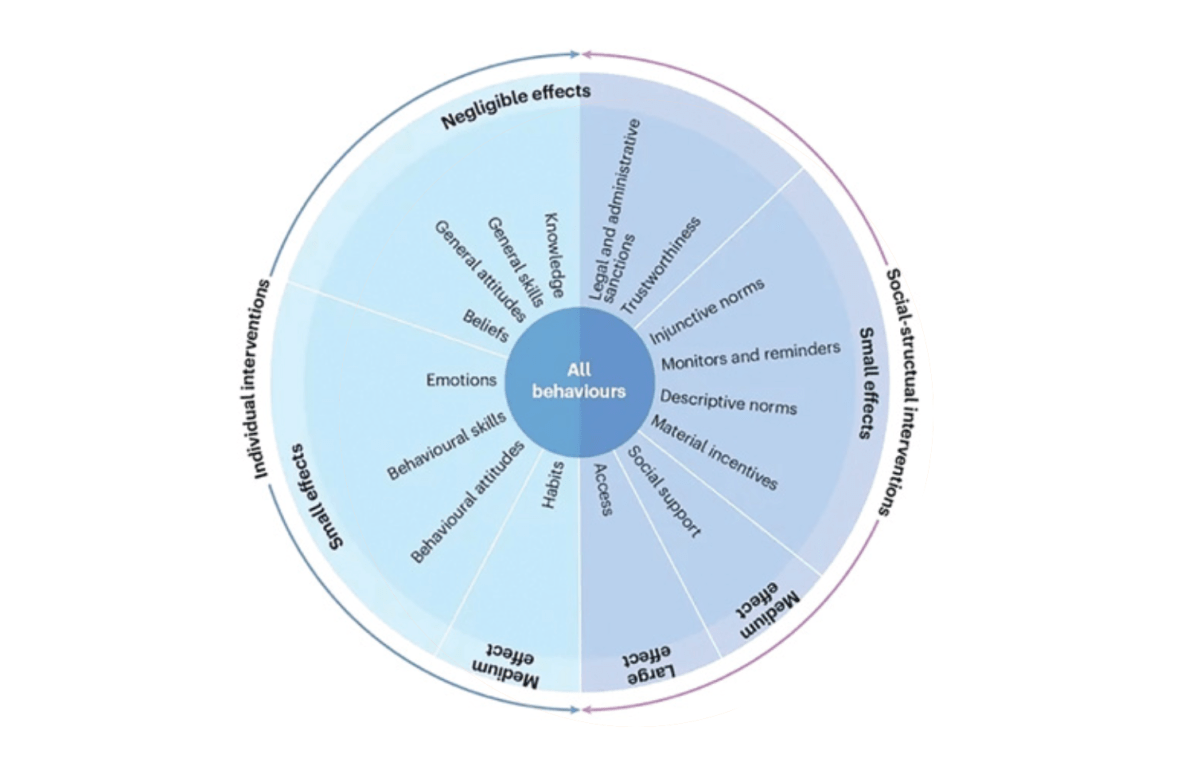

To produce evidence on what determines and changes behavior, Dolores Albarracín, Amy Gutmann Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor and colleagues undertook a review of all of the available meta-analyses — a synthesis of the results from multiple studies — to determine what interventions work best when trying to change people’s behavior. The result is a new classification of predictors of behavior and a novel, empirical model for understanding the different ways to change behavior by targeting either individual or social-structural factors.

Their paper, published in Nature Reviews Psychology, shares the strategies that people assume will work — like giving people accurate information or trying to change their beliefs — actually do not. At the same time, others, like providing social support and tapping into individuals’ behavioral skills and habits as well as removing practical obstacles to behavior (e.g., providing health insurance to encourage health behaviors), can have more sizable impacts.

“Interventions targeting knowledge, general attitudes, beliefs, administrative and legal sanctions, and trustworthiness — these factors researchers and policymakers put so much weight on — are actually quite ineffective,” said Albarracín. “They have negligible effects.”

Unfortunately, many policies and reports are centered around goals like increasing vaccine confidence (an attitude) or curbing misinformation. “Policymakers must look at evidence to determine what factors will return the investment,” Albarracín said.

Co-author Javier Granados Samayoa, the Vartan Gregorian Postdoctoral Fellow at the Annenberg Public Policy Center, has noticed researchers’ tendency to target knowledge and beliefs when creating behavior change interventions.

“There’s something about it that seems so straightforward — you think x and therefore you do y. But what the literature suggests is that there are a lot of intervening processes that have to line up for people to actually act on those beliefs, so it’s not that easy,” he said.

Targeting Human Behavior

To change behaviors, intervention researchers focus on the two types of determinants of human behavior: individual and social-structural. Individual determinants encompass personal attributes, beliefs and experiences unique to each person, while social-structural determinants encompass broader societal influences on people, like laws, norms, socioeconomic status, social support, and institutional policies.

The researchers’ review explored both of those for their ability to change behavior. For example, a study might test how learning more about vaccination might encourage vaccination (knowledge) or how reductions in health insurance copayment charges might encourage medication adherence (access). Here is what they found:

Individual Determinants

The analyses showed that what are often assumed to be the most effective individual determinants to target with interventions were not the most effective. Knowledge (like educating people about the pros of vaccination), general attitudes (like implicit bias training), and general skills (like programs designed to encourage people to stop smoking) had negligible effects on behavior.

What was effective at an individual level was targeting habits (helping people to stop or start a behavior), behavioral attitudes (having people associate certain behaviors as being “good” or “bad”), and behavioral skills (having people learn how to remove obstacles to their behavior).

Social-Structural Determinants

The researchers also found assumptions around the most effective and persuasive social-structural strategies were not true either. Legal and administrative sanctions (like requiring people to get vaccinated) and interventions to increase trustworthiness, justice, or fairness within an organization or government entity (like providing channels for voters to voice their concerns) had negligible effects on behavior.

Norms and forms to monitor and incentivize behavior had some effects, albeit small. The most effective was focusing on targeting access (like providing flu vaccinations at work) or social support (facilitating groups of people who help one another to meet their physical activity goals).

Future Use

Granados Samayoa says that knowing which behavior change interventions work at which levels is especially crucial in the face of growing health and environmental challenges.

Albarracín is gratified policymakers will now have this resource.

“Our research provides a map for what might be effective, even for behaviors nobody has studied. Just like masking became a critical behavior during the pandemic, but we had no research on masking, a broad empirical study of intervention efficacy can guide future efforts for an array of behaviors we have not directly studied but that need to be promoted during a crisis.”